A look back in time at the personal navy of the automotive icon himself, Henry Ford.

In 2019, giddy petrolheads the world over descended upon theaters to bask in the glory of a motorsport film that told the story of Ford Motor Company’s 1960’s assault on international sports car racing. Films about motorsport aren’t exceedingly common, and truly good ones are exceedingly rare. Across its 2.5 hour length, “Ford v. Ferrari” did a pretty damn good job of (albeit with the usual Hollywood “creative license”) telling the story not only of Ford’s on-track triumph over the miniscule Italian sportscar marquee at the 1966 Le Mans 24-hour race, but of the triumphs, failures and tragedies that swirled in and around its main characters at that point in history. The film no doubt deserves multiple viewings and a thorough review (it’s highlight of course being the light finally and deservedly being shined on Ken Miles), however that’s not what we’re here for today.

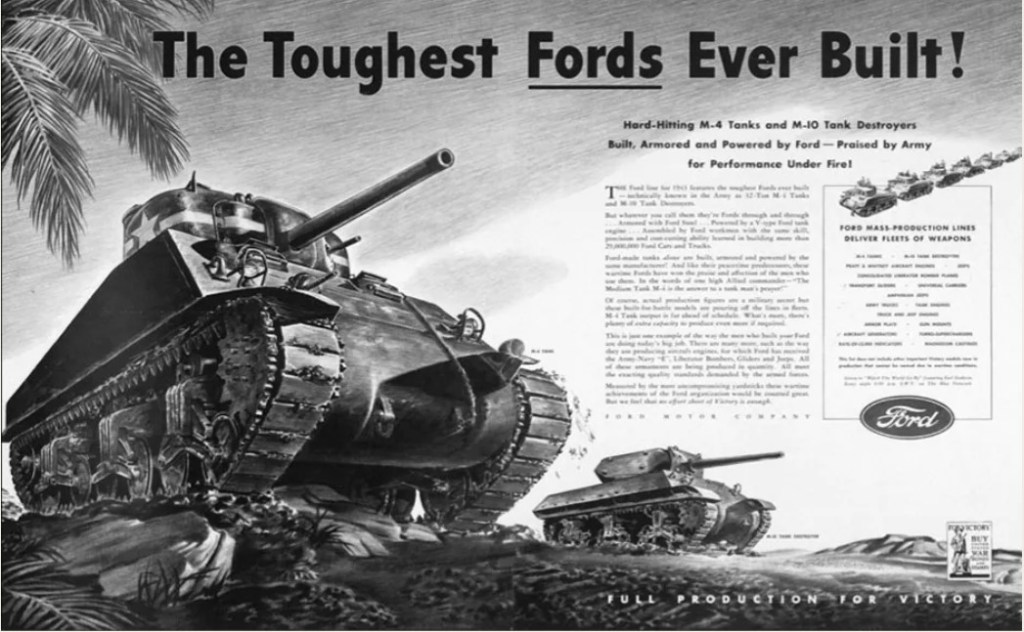

Those having seen the film might recall the scene in which Henry Ford II (Tracy Letts) lectures Carrol Shelby (Matt Damon) about how “this isn’t the first time Ford Motor Company has been to war” before admonishing the Texan to “go to war” against the famed Italian sports car company, which had so recently snubbed his buy-out attempt. The Deuce’s point about Ford having been to war before in Europe wasn’t inaccurate; Ford had indeed been to war on many fronts during both World Wars, most famously on land and in the air. But it wasn’t always intended to be that way.

PEACE SELLS…BUT WHO’S BUYING?

Company founder Henry Ford was openly and publicly opposed to World War I (and armed conflict in general), criticizing and blaming the bankers, industrialists, and others who he claimed had instigated the war. In 1915, the pacifist Ford bankrolled the chartering of the ocean liner Oscar II, which was operated at the time by the Scandinavian-American Line. The plan entailed Ford and a merry band of influential peace activists and pacifists traveling aboard the Oscar II to Europe with the intention of initiating peace talks among the warring nations. Surely the belligerents at the center of this unprecedented conflict would take note of the publicity these notable activists had generated (especially with Ford already being a powerful industrialist) and come to the bargaining table with freshly-cut olive branches in-hand.

The Oscar II, circa 1915.

Unsurprisingly, the “Peace Ship” Ford booked for his anti-war European sojourn was unsuccessful (the war would rage until 1918) and was lampooned by much of the press, who frequently referred to the Oscar II as the “ship of fools”. Not helping the cause were the frequent disagreements and very un-merry infighting amongst the would-be nautical peaceniks, coupled with Ford falling ill on the journey and bailing back Stateside less than a week after the SS Foolhardy docked in Norway. Rumor has it the questionable gazpacho served aboard the day before arrival may have been the cause of Ford’s illness, however I’ve never been able to determine if indeed a zesty chilled soup is what caused him to wash his hands of the Peace Ship ordeal and buzz back home to D-Town. Tainted vegetable emulsion or not, Ford’s dalliance with the sailing-for-peace crowd only served to reinforce his reputation for being an avid supporter of oddball causes and projects.

THE WORLD WAKES UP AND CHOOSES VIOLENCE.

By the time the United States became directly involved in World War I, Henry Ford had all but silenced his foreign policy opinions including his anti-war sentiments, with Ford now applying its various industrial strengths directly and indirectly in support of the war effort. Ford’s tractor division in England churned out unit after unit to help English farmers keep up with food supply demand in addition to producing power units for aircraft and heavy trucks. Stateside, Ford’s factories produced various weapons platforms and at least one notable aircraft engine design, the massive 27-liter Liberty V-12 (which I so badly wish would have had some kind of rad “Boss 1649” or “Super-Dee-Duper Cobra Jet” valve covers!)

Major Henry “Hap” Arnold with the first Liberty V-12 engine produced.

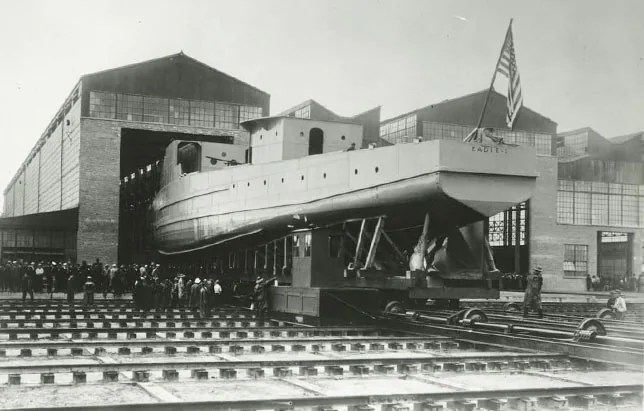

Those items aside, perhaps Ford’s most interesting contribution (or at least, attempted contribution) to the war effort came out of its sprawling Rouge River complex in Detroit. Working in conjunction with Naval engineers, Ford and his company applied their institutional knowledge of assembly line techniques to the construction of the new Eagle-class patrol craft, which were intended to combat the constant German U-boat threat in the Atlantic. Ford’s engineering contributions were fairly limited, consisting mainly of Henry’s mandate that the vessels be of simple construction, use steam turbine engines and that all steel hull plates be of the same size and shape so as to speed up production.

Ultimately these boats would not see combat service in World War I and that likely may have been a good thing considering the many construction hiccups that arose when the auto manufacturer tried their hand at ship-building, something they were decidedly not adept at. From the unsatisfactory welding and riveting of hull plates to the awkward way of launching the boats into the Rouge River, the Eagle-class boats were plagued with a litany of quality-control problems and by the end of 1918, only seven had been completed and delivered.

An Eagle-class boat emerging from The Rouge.

Eventually, a total of 60 Eagle boats were built by Ford, although their performance at sea was mixed at best. Many would end up serving in various roles other than the submarine hunter they were intended to be, from aircraft tending to photographic reconnaissance to (get this) capturing sea lions for the San Diego Zoo! The bulk of America’s Eagle boat inventory would be sold prior to its direct involvement in World War 2, although several Eagle boats flying the American flag would see service in the war with one of them being sunk by a German U-Boat off the Atlantic coast near Portland, ME in 1945.

Thankfully, Ford’s affinity for marine projects wouldn’t go down with the Eagle boats. For context, one needs to appreciate just how wide-ranging Henry Ford’s commercial ambitions were and understand just how insistent Henry Ford was on controlling every possible phase of the manufacturing process behind any and every product his company produced. From rubber plantations to soy-based plastics development to trucking and shipping, Ford was a control freak in the largest commercial sense. In the 1920’s, Ford’s controlling approach to his business ventures would manifest itself in multiple maritime ways.

THE GREAT INSPECTION

In 1925, Ford would purchase nearly 200 various merchant marine ships that the US had decommissioned in the wake of World War I’s end, with Ford scooping them up on the cheap with the intent of scrapping them. However, Ford would retain one particular ship, the MV Lake Ormoc, and convert it into a research and transport vessel fit for the high seas, complete with an eccentric captain who’d also had a hand in Ford’s ill-fated rubber-plantation-with-a-theme-park-name in Brazil (named, of all things, “Fordlandia”). The catalogue of ships owned by Ford didn’t end with the Lake Ormoc, as another ambitious project from “Henry’s Navy” in the early 1920’s arrived via some inspiration gleaned while he was on a floating vacation.

The Lake Ormoc coming alongside at the ill-fated Fordlandia plantation in Brazil.

Undoubtedly, Henry’s infatuation with floating Fords wasn’t confined to strictly military or commercial applications, though any personal watercraft he owned still seemed to serve some kind of useful business purpose to some degree or another. In 1917, Ford purchased the yacht Siala, leaving her name unchanged; he intended to use the machine for family getaways while simultaneously exploring and investigating potential natural resource opportunities like timber, mining and the like. (Editor’s Note: To my inner six-year-old, a nautical holiday exploring ways to supply my family’s industrial aspirations sounds a lot more interesting than the Osceola Cheese Factory and Silver Dollar City, which at the time seemed to be the apparent pinnacle of summertime distractions in 1980’s Missouri.)

The lovely and enticing Osceola Cheese Factory (above) and one of many exciting ride features at Branson’s Silver Dollar City (below).

Interestingly, Siala’s ownership information states that the US Navy also claimed dominion over the vessel in 1917, shortly after Ford had purchased her, with “USS” now added to her name. The Navy maintained ownership until 1920 when she was eventually re-sold to Henry Ford. Ford continued his ownership (and limited use) until 1929, when he sold her to an investment group. The Siala would change hands multiple times between 1927 and 1940, at which time the US Navy would again take ownership of the boat, rechristening it USS Coral (PY-15), the name she would bear until being scrapped in 1947. Right then, back to the early 1920’s!

Ford’s yacht Siala.

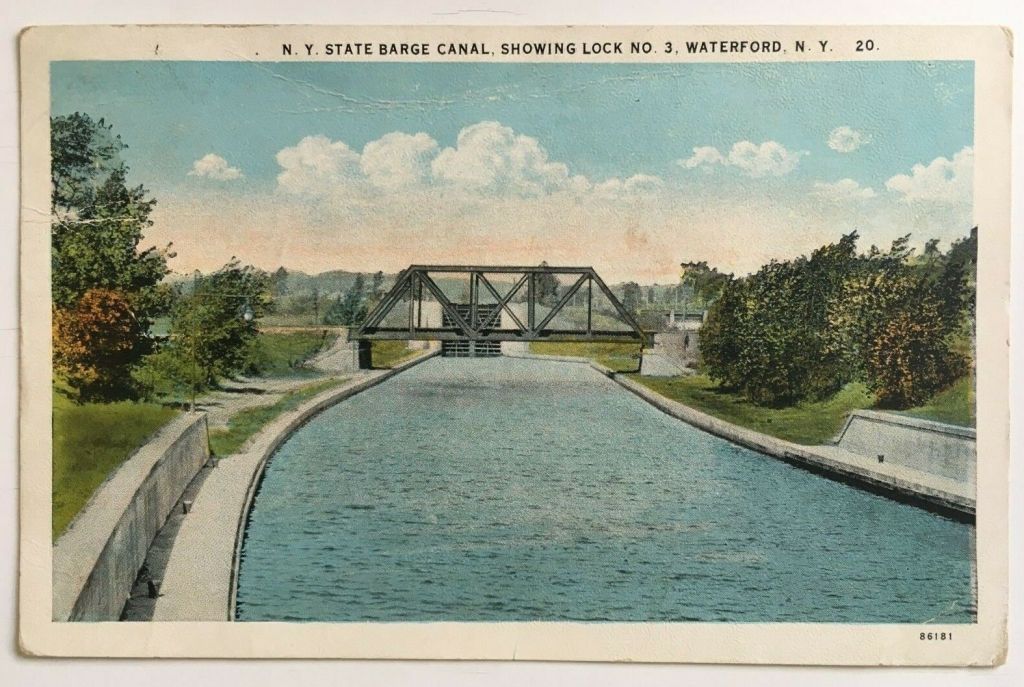

In 1922, Ford would end up on holiday in New York State as the guest of then-governor Nathan Miller, aboard a state-owned yacht named Inspector. And on this aquatic getaway, you better believe they did some inspecting…of the New York State Barge Canal. Given the opportunity to hang with the honorable Gov. Miller, why wouldn’t you inspect (and enjoy, I guess?) the New York State Barge Canal (“I know I would!” – Harray Caray, probably). The Barge Canal was completed in 1918 after 13 years of construction, with the goal of enhancing water-borne commerce and transportation by improving on existing canal networks (namely the Erie Canal) while also expanding to better utilize existing rivers that the Erie Canal’s builders had avoided, like the Genesee and Seneca rivers. But enough canal contextualization for a moment…back to Henry’s trip.

An antique postcard depicting a bridge and Lock #3 near Waterford, NY on the New York State Barge Canal.

On the trip in question aboard the Inspector, Ford would get to, erm, inspect the Champlain Division of the Canal network as the governor’s guest before spending a weekend with his family at their cottage on Lake George. At the conclusion of his brief retreat, Ford hailed the 1920’s version of a sailorly Uber for industrial tycoons, linking up with his son Edsel aboard his private yacht, Greyhound, for a ride home to Detroit. Together they motored their way back to the Motor City, navigating the impressive canal network before emerging (presumably) around Oswego, NY followed by lengthy runs across Lake Ontario and Lake Erie. Ford, ever the opportunistic industrialist, saw this winding canal system as a potential commercial hallway that could help connect his Great Lakes-region operations with other Ford plants and facilities on the Eastern Seaboard.

Edsel Ford’s Greyhound.

Quick sidebar: Around this same window of time, in late 1923/early 1924, Ford commissioned the Hacker Boat Company (owned by a life-long friend of Ford) to work jointly with Ford itself to produce an absolutely exquisite-looking 33ft-long wooden boat, powered by no less than a 27-liter Ford V12 aircraft engine, producing 450hp and a terrifying 1,250lb-ft of torque. Styled with a restrained wrap-around windshield, louvered engine-cover doors, and a 4-bucket seat cockpit arrangement (left hand drive!) that truly reflects the timeless styling of that period. Named Evangeline, apparently after Ford racing driver Raymond Dahlinger’s wife. Legend has it that Evangeline was a long-time Ford employee and a close friend of Henry’s, personal secretary, in his inner circle, influential to him, all of that. Sounds scandalous, so maybe naming a 33-footer powered by an engine originally designed to lift planes off the ground is fitting.

Recent photos of the immaculate Evangeline, at speed (top) and revealing her Liberty V-12 powerplant (bottom).

Years later as 1930 gave way to 1931, Ford would dispatch a squad of trusted design engineers to New York’s capital city of Albany with the intended goal of meeting the state’s canal officials, a proposition in-hand from the big man himself. In this proposal were details surrounding Henry’s plan to operate a fleet of specially-designed motorships, part ship, part barge, that would ply the canal system. Perhaps recalling some of Ford’s early nautical design failures, renowned naval architecture concern Henry J. Gielow, Inc. of New York was enlisted to design the unique vessels.

At a tick over 300ft in length, these vessels would be the largest ever built to work on the New York State barge canal system. The keels for these turbine-powered boats (another first) were laid down the same year, at where else but the Great Lakes Engineering works in River Rouge, Michigan. No matter how short your ship, there’s always going to be a low bridge or two (or 40+) somewhere along the way that you risk banging your mast into while underway. Knowing this thanks in part to his intense inspection of the stock market-sounding NYSBC, Ford and his designers developed a retractable pilot house arrangement that allowed the entire unit to raise and lower into a well in the ship’s hull, like an elevator moves up and down in its shaft. In addition to the moveable helm, other protrusions like turbine exhaust stacks and miscellaneous poles and masts also could be lowered down close to the deck to assist in maintaining overhead clearance.

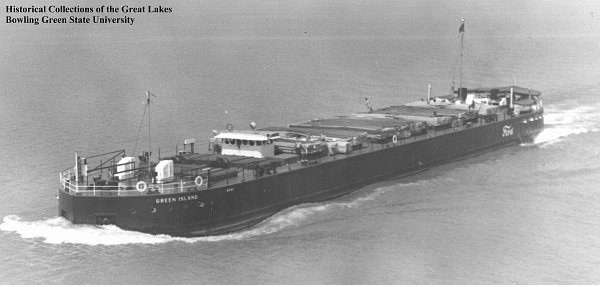

Ford’s canal motorship, the Green Island.

Each of these bespoke craft broke with tradition when it came to controlling the vessel, giving the helmsman hands-on governance over primary functions like steering and engine orders for their two Westinghouse 800 horsepower oil-fired steam turbine engines. At the time, a system of bells was commonly used by ship’s pilots to signal their control directives to the crew, so the inclusion of a control-centric pilothouse was rare but forward-thinking for the time. With 1600HP on tap, Ford’s motorships could make just over 11 knots (13mph) while carrying nearly 2800 tons (560,000lbs, if my math serves), loaded through nine different cargo hatches.

The Norfolk canal barge motorship.

As they had throughout the entirety of the design process for these motorships, Ford’s engineers took into account the confined nature of the NYSBC’s operations and outfitted the vessels with multiple systems that enhanced their low-speed maneuverability, such as dual rudders and direct-reversing engines. All of this said, don’t think for a moment that these vessels were bound to the confines of the NYSBC; Ford and his designers also intended for these motorships to safely navigate the much more challenging, deeper waters of the Great Lakes and even the Atlantic Ocean, broadening their reach from points west like Duluth to as least as far east as the Canadian Maritimes or the US eastern seaboard.

The first two motorships in this new class of vessel would be christened the Chester and the Edgewater, on May 9, 1931 and May 16, 1931 respectively. The Chester was so named for the Ford plant in Chester, PA (near Philly) that the crafts would service, while the Edgewater owed its namesake to the Edgewater, NJ Ford plant situated across the Hudson River from NY’s West Harlem neighborhood. By mid-1931 the twin vessels were fully shook-down and ready for service, tastefully-emblazoned with the “Ford” cursive script on each side of the hull near the stern.

America’s Great Depression was well underway by 1931, so it’s no overstatement to say that the Chester and Edgewater were welcome additions to Ford’s business, particularly in the way they aided Ford in developing their export market while also allowing them to contract the vessels out to haul various bulk commodities for outside companies. All of this kept their 22-person crews busy working virtually 24-7 and their usefulness didn’t go unnoticed; Ford would double his canal fleet’s size in 1937 with the addition of two more of the unique motorships.

The Chester working its way through a lock on the NYSCBS.

With lessons learned from years of successful operations using the original canal ships, these new additions featured a slew of refinements and changes including repositioned pilot houses, reshaped hull sides and a switch to a pair of all-new Cooper-Bessemer diesel engines, combining to produce a more reliable and economical 1200HP. Further still, these new vessels would be the first freighter of any kind on the Great Lakes to feature a 100% welded hull construction, completely eschewing traditional riveting methods. The technique of welding up a ship’s hull in this fashion was a trailblazing way of constructing a ship, and ultimately would prove to aid the US greatly in the rapid, hasty construction of cargo ships during the next world war that lurked just over the horizon.

THE WORLD CHOOSES VIOLENCE…AGAIN.

As the world-changing fury of World War II washed up on America’s shores, the US Navy once again dipped its ladle into Ford’s pool of resources and requisitioned the four canal vessels. The Navy deployed them somewhat confusingly to the blue water of the Caribbean Sea instead of keeping them working the lakes and canals they had already proven to be so efficient at moving cargo along. This decision cannot be called anything but ill-considered; the entire purpose of these ships, the Great Lakes system and the NYSBC system was to transport cargo to and from virtually any port on the Great Lakes and the eastern US seaboard without having to cross-load cargo across multiple vessels. Instead, the US Navy’s decision robbed the New York State Barge Canal of the only vessels specifically designed to operate efficiently within its confines, forcing the boats to operate exclusively in open ocean waters rather than leaning on their ability to do so only for parts of a journey.

All would not be well for the Green Island on its trip to the Caribbean.

In 1942 the Navy considered the Caribbean to be safe waters, however the captain and crew of one of Ford’s second-gen canal boats, the Green Island (named for Ford’s Troy, NY plant) discovered to their dismay that they were not in fact safe at all. Due to the canal boats’ low profile, particularly in low-light, they could easily be mistaken for a diesel-electric submarine floating on the surface. Early one January morning in 1942 off the coast of Florida, the US Navy destroyer USS Hamilton mis-identified the Green Island and actually rammed the canal boat (“damn the torpedoes, let’s just use the whole ship instead!” said the captain, probably), damaging the cargo carrier and forcing her to the port of Miami to make repairs.

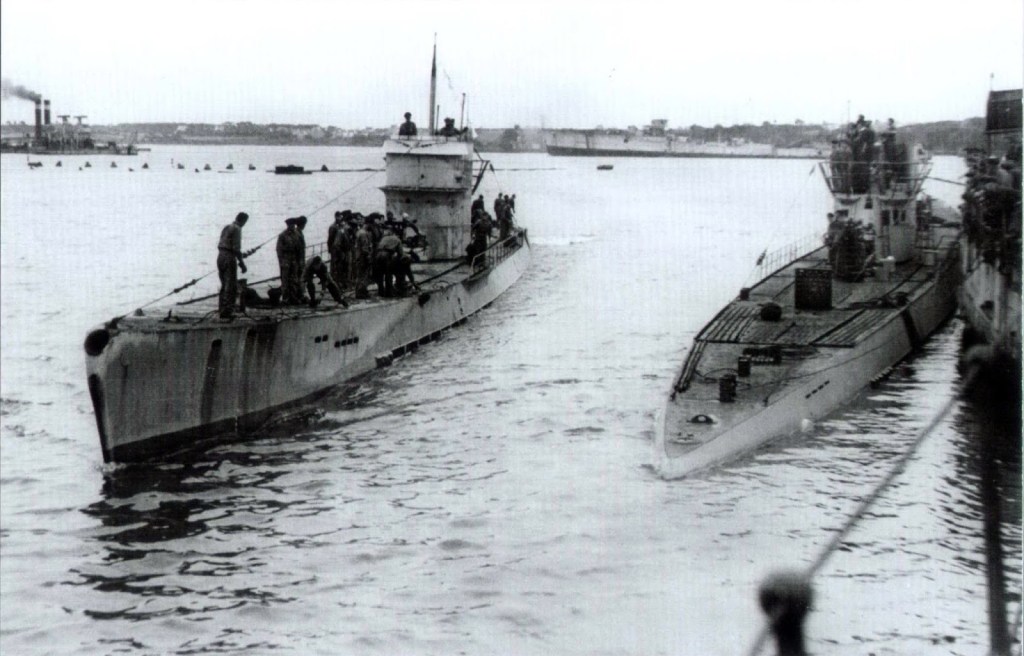

U-125 (left) returning to the Lorient U-Boat base following a string of missions during WWII.

Seemingly just days after reentering service following its repair stint in Miami, the Green Island met her end at the hands of the Nazi U-boat U-125 (which was ironically sunk a year later to the day in the North Atlantic, thanks to our homies with the Royal Navy). The Green Island was returning stateside with a load of sugar (and probably some cigars, maybe) from Cuba when the German submarine set about sinking her. Proving that truth is often stranger than fiction, the U-boat’s captain ordered the Ford boat’s crew into their lifeboats before sending a fatal torpedo hurling into her hull between the 4th and 5th hatches, about six feet below the waterline. As the former canal freighter fell to rest on the floor of the Caribbean, the U-boat captain’s unusual show of compassion for the merchant seamen allowed the entire 22-person crew to survive in their lifeboats for about a day before being rescued by a British merchant steamer.

Thankfully, the remaining three Ford boats would survive the duration of the war, contributing as best as they could for a small fleet of fish who were distinctly out of their intended water. The immense changes and economic obstacles that industrial giants like Ford overcame during World War II greatly affected how they approached doing business post-war, that much is certain. With those changes came shifting business practices and priorities and by war’s end Ford had decided to dispose of its canal fleet, which had been modified during the war to the point they could no longer ply the Barge Canal system. The Chester would be scrapped in the mid-1950’s by her Brazilian owner; the Norfolk was operated by a Canadian concern until she went to scrap in 1967; and lastly, the Edgewater worked the Great Lakes until sinking to the bottom of Lake Erie in 1968, taking with her the last remnants of Henry Ford’s New York State Barge Canal fleet.

That wouldn’t be the end of the Ford family’s fleet activities, though.

HENRY LIKES BIG BOATS AND HE CANNOT LIE.

The next chapter in my discombobulated rambling history of Ford’s fleet deals with the largest, most striking, and unquestionably coolest members of the family’s flotilla. For this, we must again travel back in history and return to the 1920’s, around the point in time when Henry had purchased leftover World War I ships for scrap.

It’s not hard to imagine that if Henry Ford was to have purchased pre-made vinyl decals for his home’s kitchen walls, “Live, Laugh, Love” would have been immediately passed over for the more appropriate (if lesser-used) “Efficiency, Synergy, Control” decal set. It should be abundantly clear by this point in the story that those three things were always at the front of Henry’s mind, and he was truly a master of weaving them together.

A vintage postcard depicting Ford’s Rouge River Complex.

Now, while the efficiency of the workhorse barge canal ships Henry controlled and the synergy that they helped provide was impressive, the plucky little 300ft-long units weren’t ideally suited or substantial enough for moving truly large amounts of cargo across the Great Lakes. All five of these inland seas could grow notoriously hostile in times of inclement weather, as hundreds of ill-fated vessels have discovered over the centuries. Ford needed to move coal from places like Toledo and iron ore from ports farther north and west in vast quantities, enough to fuel the massive Ford steel mills at Rouge River in Dearborn, just southeast of downtown Detroit. This all but dictated that a dedicated fleet of bulk carrier ships (properly called “boats” in Great Lakes parlance) would need to be procured.

In 1923, Ford’s team completed what they called the “river navigation project” at The Rouge, allowing relatively ample space for moving material in and out of the property by water much more efficiently than before the project. In conjunction with the City of Detroit and Wayne County, multiple moveable bridges like the famed West Jefferson Avenue bascule bridge were installed as part of the project, while a turning basin and a thorough dredging/deepening of the Rouge River were also completed, all of which would allow the giant freighters to access to Ford’s Rouge River Complex. Quickly Ford and his team realized that their facility was so large that a contracted freighter here and there wasn’t going to be enough to keep the place running properly. Henry needed to acquire his own freighters, and he quickly set about doing just that.

The Benson Ford unloading at The Rouge.

At over 600 feet in length and named for his grandsons, the SS Henry Ford II and the SS Benson Ford were commissioned in 1924, forgoing the contemporary choice of coal-fired steam propulsion in favor of advanced British-designed diesel engines. Built by Sun Shipbuilding in Philadelphia under license from British concern Doxford, each 4-cylinder, two-stroke diesel engine made over 3,000HP. The Benson Ford was launched from Great Lakes Engineering works in Escorse, MI on April 26, 1924, after the Henry Ford II had launched nearly two months prior on March 1 at American Ship Building Co. in Lorain, OH. These were the first two major vessels on the Great Lakes to employ heavy diesel power.

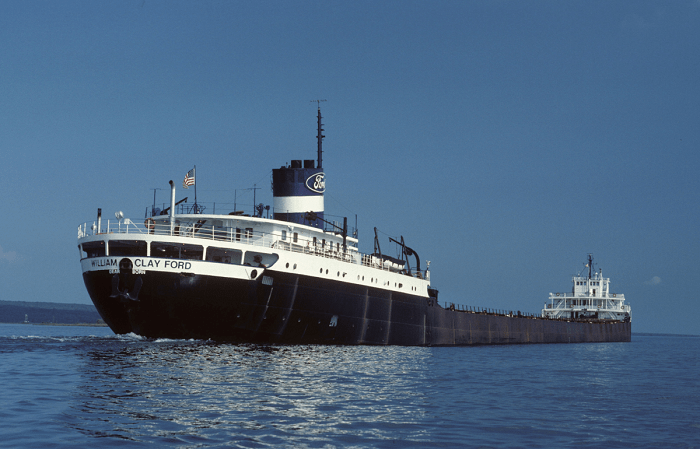

The William Clay Ford underway.

Regardless of the fact that Ford owned and had access to many yachts around that time, he would insist that both freighters come fitted with large, comfortable staterooms and other amenities. This permitted he and his wife Clara (or other dignitaries and VIPs) to travel aboard the freighter on its journey, often times using the boats to get to and from their vacation home in Northern Michigan. Keep that in mind, as those large state rooms will come to play again later in the story.

In spite of their size and capacity, Ford’s war-time and post-war growth was such that the Benson Ford and Henry Ford II alone couldn’t keep up with demand for raw materials at The Rouge. Because of this, in the early 1950’s the “new Ford Fleet” was commissioned, an eight- vessel expansion which notably included the SS William Clay Ford. Churning the waters of the Rouge River with 7,700 steam turbine-driven horsepower and a maximum capacity of 21,000 tons, the William Clay Ford could make way along the open waters of the Great Lakes at a respectable 14 knots, or about as fast as a fully-loaded modern cruise ship will tend to sail at.

As far as I’ve been able to ascertain, all of Ford’s freighter fleet hovered around the 650ft length mark, or just under. A series of locks connect all of the Great Lakes (except for Michigan, which requires no lock for boats to come and go) and understandably there’s a size limit for vessels wishing to use them. While the Soo Locks at Sault Ste. Marie, MI can accommodate boats in the 1,000ft range, the Welland Canal in Ontario near Niagara Falls connects Lakes Erie and Ontario with a series of eight locks that limit vessel size to about 740ft.

Few people that I’ve met outside of the Great Lakes region are aware of American and Canadian freighter boat operations on the Great Lakes and how to this day it remains a vital part of North America’s economy to the tune of $35 billion in economic activity and 200,000 jobs in 2021. Occasionally I’ll encounter someone, generally above a certain age, who recalls Gordon Lightfoot’s stirring 1976 folk single, “The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald”, which chronicles the tragic 1975 sinking of the 729ft freighter Edmund Fitzgerald in stormy weather on Lake Superior. A part of the story Lightfoot wasn’t able to tell (despite the song’s hefty 6-minute running length) was that of the William Clay Ford and fellow freighter Arthur M. Anderson being the first two ships involved in the search for the Fitz.

An artist’s depiction of the William Clay Ford fighting rough seas while conducting SAR in the wake of the Edmund Fitzgerald disaster.

A monumental storm was wreaking havoc on Lake Superior on the night of November 10th, 1975, bringing hurricane-force gales and rogue waves exceeding 35ft in height. The Arthur M. Anderson and the William Clay Ford had reached the relative safety of Whitefish Bay near Sault Ste. Marie, but contacthad been lost with the Fitz and it was suspected that the boat may have broken up and/or capsized and sank, so the US Coast Guard requested that the Anderson and the Ford turn around and attempt a search for survivors. Ultimately, none of the Fitz’s 29 crew members were found that night, or ever; only debris floating on the surface was found in the days that followed. It would be four days before a US Navy P-3 Orion antisubmarine aircraft, equipped with magnetic anomaly detectors (normally used to find submarines underwater) located the Fitz’s final resting place, broke into nearly equally-long pieces at the bottom of 530ft of water. The tragedy of the Edmund Fitzgerald was a stark reminder to mariners across the globe, and especially those like Ford’s boat crews on the Great Lakes, that sailing carries inherent risks no matter the size of the vessel.

An aerial view of The Rouge in the early 1970’s. Note the three freighters conducting unloading operations alongside.

As ever, Ford’s strategy for doing business both in the US and globally would continue evolving over time, thanks to factors both internal and external. The dual threat of competition, domestic and foreign; a fuel/oil crisis in the 70’s; increased use of plastics and other alternative materials in car building, and an aging fleet of freighters caused Ford Motor Company to dwindle the size of its Great Lakes fleet to the point that by the late 1980’s they were out of the game altogether. Some of their fleet had been sold off to other ownership, while others sadly found their way all too soon to the scrap heap. Yet, despite all of the changes and culling of the herd, a couple pieces (literally) of Ford’s Navy would find a way to live on….on land.

GREAT LAKES FREIGHTERS, NOW 100% LESS FLOATY!

Picture yourself in a reasonably comfortable, air-conditioned hotel room. Something like a Best Western that’s been recently renovated and is cared for by upstanding owners. Maybe it’s a hot Midwestern evening, and you’ve just called it quits for the day after a long 14-hour stint behind the wheel. Maybe the AC is hitting just right and you decide to sit back in your room’s minimalist desk chair and do some research on nearby culinary options that might make for a more interesting dinner than the hotel’s adjacent Applebees (save 10% with your room card!). Maybe you instinctively flick the TV on and start channel surfing with one hand while you peruse Google Maps with the other. Maybe you accidentally land on one of those HGTV-style shows showcasing wacky homes and the whack-jobs that often own them. You know the show, it’s like an episode of Diners, Drive-Ins & Dives but it’s missing a flamboyant host like Guy and you’re pretty sure that most of the home-owners on the show have used LSD more than once. And maybe…just maybe you’ve landed on the episode where the Benson Ford shiphouse is featured.

“Brother, this shiphouse is off the chain!”

No, I didn’t misspell a crude euphemism for the bathroom (or more properly, “head”) on the Benson Ford. No, it’s not a ship-inspired home named after the former Ford freighter. No, my friends, this is the real effing deal. Like something that should be at a maritime museum (hold that thought…), some ambitious soul literally had the entire forward cabin and helm structure, along with a sizeable chunk of the upper bow of the Benson Ford torched off the hull and made into a cliff-side vacation home, leaving intact virtually all of the antique poshness and rugged lake-faring charm that comes with a piece of nautical history possessing some serious pedigree.

The year was 1986. The 80’s were very much still the 80’s, hair was still very big, Simmons electronic drums were in vogue, and some people with money really, really liked spending that money, and also maybe trying some cocaine. Frequently. I’m not saying that Frank J. Sullivan, the dude who bought the Benson Ford (renamed the John Dykstra II after leaving Ford’s ownership) in 1981 upon its decommissioning, was any sort of an enthusiast when it came to nose candy. Nothing would change my mind about that, not even the fact that in the aforementioned year of 1986, he had the forecastle of the Benson/Dykstra removed and transported by barge to South Bass Island (also known as Put-In-Bay, apparently. Maybe those were the instructions to the barge operators?). It was then lofted up by crane onto the shore, coming to rest atop a short cliff above the waters of Lake Erie. At the conclusion of its brief airborne sojourn, it was somehow secured (anchored?), wired, plumbed and otherwise converted legally into a 4-story house.

After Frank came down got turned down in 1992 by the local zoning board when he petitioned to convert the former lake boat into a bed & breakfast, he decided to sell the shiphouse at auction, where it was picked up by Jerry and Bryan Kasper, who are apparently still the owners today (I feel like I saw on TV somewhere that these guys made their money selling cars or something…). I’m not sure what sort of potent potable a person might fortify themselves with before walking out the door while hollering “Honey, I’m heading to the auction to buy a ship’s forward superstructure that’s been converted to a house on an island that can’t be reached by a bridge, I’ll be back before dinner!” over their shoulder, but I imagine it must be formidably strong.

According to the owner’s website, the shiphouse is 7,000 square feet of pure vacation home, equipped with five bedrooms, five full baths, a full kitchen and dining room, a family room, a garage (not original equipment, I’d imagine) and of course the requisite pilothouse. The original walnut-paneled staterooms harken back to the days when Henry Ford himself was spec’ing these out (shame that Ford didn’t have a “Build Your Own Great Lakes Freighter” feature on their website back then), with the full intention of taking cruises aboard with his family. As one of the richest men on the planet at the time, it’s an interesting look back at what tastes were like then, especially those of a magnate like him.

Perhaps owing to these boats’ pedigree as some of the most notable vehicles without wheels ever to bear the Ford namesake/badging, a second Ford freighter found part of its forward structure being saved from the scrap heap, literally and historically. Apparently if you were the forward superstructure of a former Ford boat in 1986, it was an eventful time because the same year that the Benson Shiphouse Project (sounds like a bad-ass English prog band name) was underway, the William Clay Ford had its own pilot house structure removed and installed as an exhibition at the Dossin Great Lakes Museum on Detroit’s Belle Isle, before the hull was sent for scrapping at Port Maitland, Ontario the following year.

BREAK OUT ANOTHER THOUSAND

More like 5,000! There’s a joke in the watercraft ownership community (or so I’m told, I don’t own one) that “boat” is actually an acronym, “B.O.A.T.”, and it stands for “Break Out Another Thousand”, referencing the constant (large) expenditures that come with owning a boat or other personal watercraft.

For me, I’d have to break out several thousand more words to truly touch on all of Ford’s waterborne ventures, as there are many I’ve not even addressed in this piece, a piece which constitutes a mere window-shopping-look at the deeper history behind Ford Motor Company’s floating enterprises and undertakings. Staggeringly, all of that is but a tiny historical slice from a pie on the bottom counter of the entire company’s larger desert case. And that makes me wonder, did any of Henry’s boats feature a dessert case in their galley? If so, I guarantee they didn’t serve humble pie.

Research Sources & Thank-You’s: New York Almanack, TopGear.com, Mac’s Motor City Garage, TheHenryFord.org, GreatLakesVesselHistory.com, Wikipedia.org, ShipOnTheBay.com, ShipSpotting.com, Tugster: A Water Blog, Detroit Historical Society, Ford.com, Digital Commonwealth: Massachusetts Online, Blogging By Cinema Light, Google, Google Images, Google Maps,