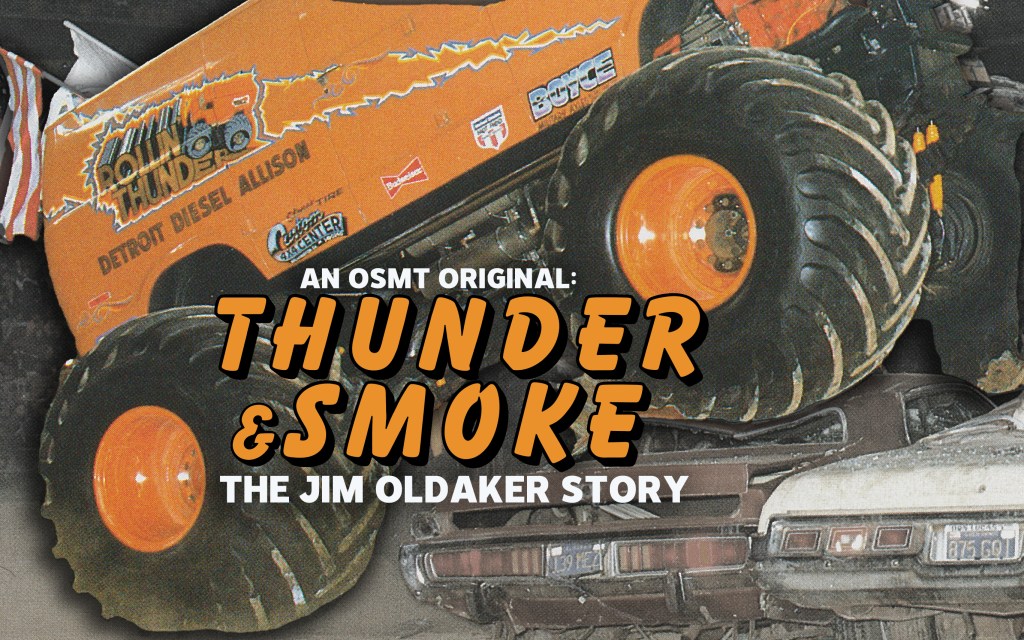

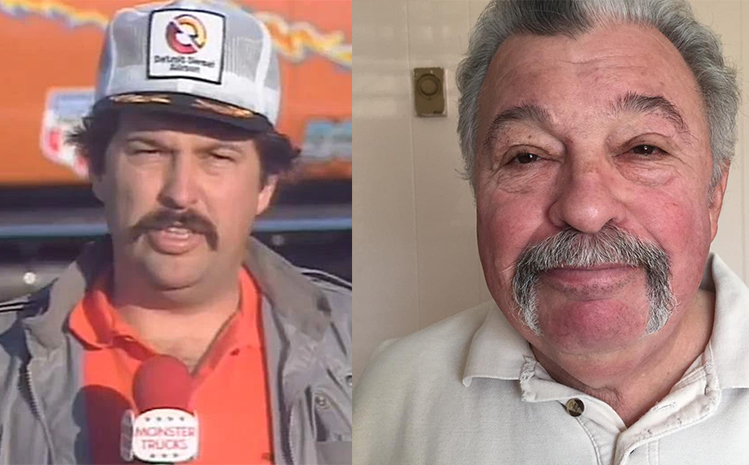

Maybe you know the truck. You might not know the name. You definitely don’t know the whole tale. This is the story of Jim Oldaker, creator of the legendary Rollin’ Thunder.

Editor’s Note: Well kids, this one ain’t a short one. Turns out Mr. Oldaker has quite the life story, and I wasn’t going to cut anything out if I could help it. I hope you enjoy reading about his extraordinarily unconventional life. This is Part 1 of 4, of “Thunder & Smoke: The Jim Oldaker Story, an OSMT Original.” I have gone to great lengths working with Jim, and conducting hours upon hours of research to make this piece as accurate as I possibly can. Any discrepancies are purely by accident, but it is my sincere hope that I have told Mr. Oldaker’s incredible story as faithfully as possible. -Kyle Doyle, August 19th, 2024

Twist & Shout: Kansas City – November 1984

“POP!”

The term “military-grade” gets bandied about a lot as a marketing tool for consumer goods, ranging from night vision goggles and electronics to overpriced coolers and paracord keychains. “Our super-scary Punisher-style truck window decals are made from military-grade vinyl, so they won’t peel or fade while you’re parked in a mall parking lot!” In reality, “military-grade” doesn’t always denote that something actually is tougher, more efficient or of higher quality and durability.

Don’t believe me? Just ask someone who’s served in the US military and they’ll probably have enough stories of inferior and failure-prone equipment to make you want to puke up that military-grade MRE lunch that has been lodged in your gut you since you ate it while camping a week ago. Famed USMC pilot and NASA astronaut John Glenn was once asked how he felt while strapped into his Mercury capsule perched high atop an Atlas rocket, waiting for his journey that would see him become the first American to orbit Earth.

Glenn’s answer?

“I felt exactly how you would feel if you were getting ready to launch and knew that you were sitting on top of two million parts – all built by the lowest bidder on a government contract.”

“POP!”

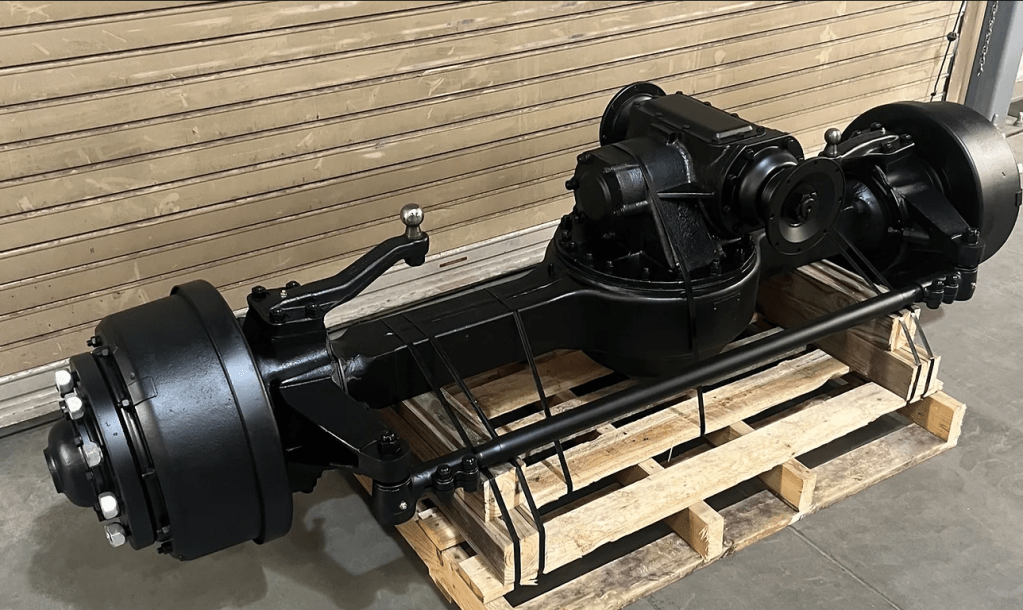

Still, much of the “mil-spec” or “mil-grade” stuff that made its way from surplus to showbiz in the monster truck industry during the 1980’s was fairly robust. Truck frames, transfer cases and even tracked vehicle “tank” chassis found their way into the industry in increasingly larger numbers as the decade wore on. These components helped form the starting point of countless monster truck builds, giving untold numbers of fabricators some of the key building blocks they would need on their journey to potential car-crushing stardom. However, no single part, piece or platform could likely be found in as widespread use across the industry by the mid-1980’s than the ubiquitous Rockwell 5-ton truck axle.

The Rockwell-Standard Corporation’s roots can be traced back to a small axle plant founded in Oskosh, Wisconsin in 1919 by a Colonel Willard Rockwell. The company manufactured truck axles and components for the US Military and in 1928 they entered a merger with the Timken-Detroit Axle Company (all of these names should sound at least vaguely familiar to any good auto enthusiast). When the International Harvester company rushed the new M-39 series 5-ton heavy tactical truck into production in 1951 for the Department of Defense, Rockwell’s axles were underneath them.

“POP!”

Equipped with a double-reduction “top-loader” style ring & pinion center section, these 5-ton axles typically featured a 6.44:1 final drive ratio that allowed the stout 2-inch-diameter axle shafts to easily turn the heavy tire and wheel combinations required by the US military, even on difficult terrain while under heavy load. But as more and more of these axles (and the trucks they were attached to) became government surplus and made it out into the civilian world over time, their legendary strength caught the eye of a small group of very serious off-road enthusiasts.

These mechanical alchemists had already discovered the shortcomings of smaller axles (including the 5-ton’s baby brother, the Rockwell 2.5-ton) and were ready to step up to something bigger, stronger, and beefier. They quickly assessed that the Rockwell 5-ton axle would offer them a truly bullet-proof solution for their massive 4×4 projects (which had recently been nicknamed “monster trucks” by one savvy promoter), something that wouldn’t break under the strain of repeated mud bog runs, sled pulls and car crushing exhibitions.

And while they weren’t totally wrong, they weren’t exactly 100% correct in this assessment either.

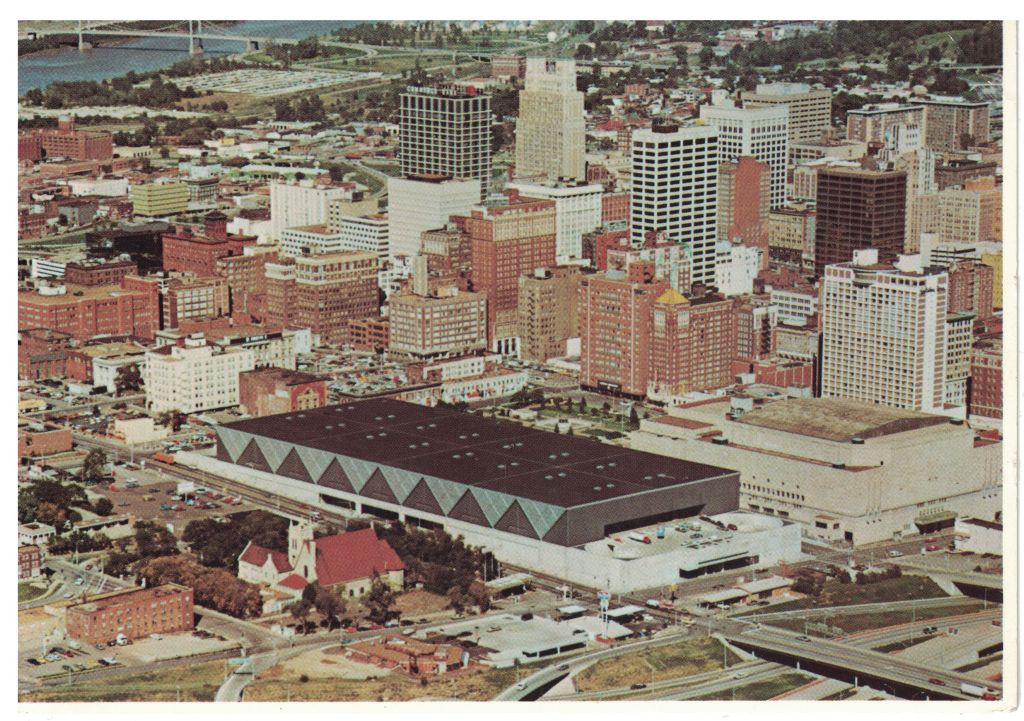

“POP!”

That loud, metallic “popping” noise is the sound of a 2-inch-thick military-grade Rockwell 5-ton axle shaft snapping, the fourth and final nail in the coffin of the night’s attempted performance by an 18,000lb leviathan called “Rollin’ Thunder.” It’s Thanksgiving Day, the 29th of November 1984, and Jim Oldaker, driver of the Rollin’ Thunder monster truck, is struggling to find much to be thankful for at this moment apart from the fact that his performance inside downtown Kansas City’s Bartle Hall Convention Center is essentially over. There will be no turkey and stuffing this evening, no pumpkin pie for dessert. And definitely no falling asleep in the recliner watching the Dallas Cowboys and the Detroit Lions sneak past the Patriots and the Packers respectively, each by a narrow 3-point margin. Tonight, there’s just work. More work.

The strain on Oldaker’s mind and body is painfully visible at this point to bystanders, from the knicks and bruises on his hands to the darkening circles under his eyes that clearly indicate a serious lack of rest over the previous days and nights. An amalgam of dirt and petroleum-based residue has stubbornly occupied the space under his battered fingernails, but he ignores this fact as his fingers fumble for the zipper on his trusty, grease-stained coveralls. He’ll soon depend on these coveralls to help stave off the chill of a cold Midwestern night that is diving towards freezing at the rate of about a degree per hour. Rollin’ Thunder’s spare outer axle shafts are in a toolbox on his trailer, which is parked none too conveniently outside the multi-story convo center.

“The hell have I gotten myself into?” Oldaker mutters to himself as he trudges outside for tools and parts, instead of trudging back in the opposite direction to his warm and inviting hotel room. He might have muttered the curse, but he wanted to shout it at the top of his lungs. These are just the latest steps in this particular journey, one fraught with frustration and sleep-depravation that began more than 1,600 miles and several days ago in the sunny port city and LA suburb of Long Beach, California. In all reality though, the events of this night in 1984 are taking place not all that far from the very nucleus of Oldaker’s story, a story that has never been completely told until now.

A Call To Grand Lake – Cheyenne & Grand Lake – June 2024

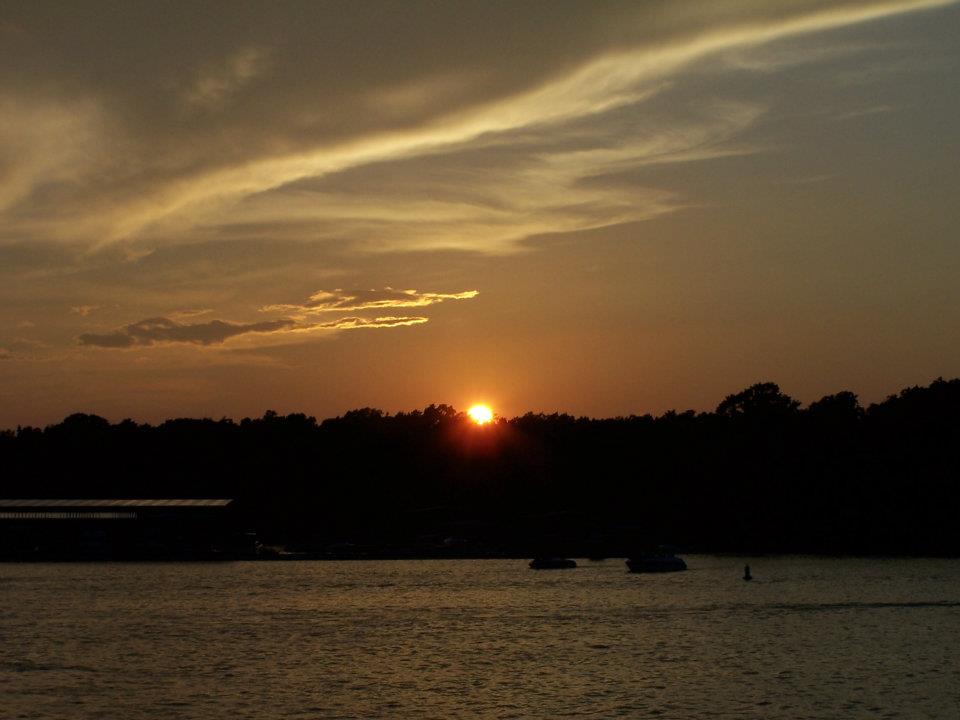

Constructed between 1938 and 1940, the Pensacola Dam in northeast Oklahoma stretches a staggering 6,565ft in total length and is said to be the longest multiple-arch-type dam in the world. Its 51 arches have helped to constrain the waters of the Neosho River which in turn have formed the Grand Lake o’ The Cherokees, colloquially known as simply “Grand Lake” by locals.

It’s now been nearly four decades since that cold Thanksgiving night in Kansas City, the city I was born in and once called home. Jim Oldaker is now at his home on Grand Lake and is retired, both professionally and for the evening. The sun is closing out its duties for this part of the globe as the clock shows it to be just a few minutes before 7:00pm local time. The oppressive summertime swelter of this western-most zone of the Ozark region is starting to release its grasp for the evening and the muggy, wet-rag-on-your-face humidity of the daytime has been replaced by a slightly kinder, cooler version of the condition. Perfect conditions for sitting on the porch in a comfortable chair, imbibing in a chilled beverage and soaking up the sound of crickets and katydids engaging in their pre-nocturnal chorus.

If you’d have asked me as a kid (who spent many a summer on the Lake of the Ozarks in central Missouri) if this transition from light to night was my favorite part of the day, “yes” almost certainly would have been my answer.

Perhaps it is the same for Oldaker as well, but tonight his plans have changed; much like that night in Kansas City, there’s work to be done. I’ve rushed through my evening routine with my family (hugs, homecooked meal, high-fives, etc) and now I’ve retreated to the sanctity of my garage/bar/hang-out space in the city I now call home, Cheyenne, Wyoming, so I can be on a call with Jim promptly at 6:00pm Mountain/7:00pm Central.

If you’d have asked me as a kid in the late 1980’s if I’d ever get to interview Jim Oldaker of Rollin’ Thunder fame, “no” almost certainly would have been my answer. But here we are.

The Crossroads to Green Country: Vinita – 1953

Jim and I have been connected on social media since September of 2013, but apart from some occasional direct message chats or comments on the same thread, we’ve never had much direct contact and certainly we’ve never taken the time to chat on the phone, much less meet face to face. How do you greet someone you’ve “known” for over a decade but really don’t know? And how do you even convince them to tell you their life’s story on the phone? Well, I’d have to venture a guess that the shared experience of being a road-weary monster trucker can span a lot of time, age, and distance gaps.

We exchange the usual greetings and pleasantries and Jim’s voice is that of wise, friendly grandfather-figure we all wish we had as kids growing up (and still wish we had today). Devoid of any specific accent (call it “American Midland”), he seems both bemused and confused as to why I’ve decided to write about his story, and his skepticism can hardly be blamed in this day and age where personal privacy seems to be at an all-time low and anything on the internet “exists forever.” I do my best impression of a conversational icebreaker and before long, chunks of stories start to chip away from his icepack of memories and I’m soon taking notes just as fast as my hands can type.

“Well, I was born in 1953 in Vinita, Oklahoma,” explains Oldaker, “but we didn’t live there very long before we moved to California. I think I was around three years old when my mom and step-father moved us out to the West Coast. I didn’t have any siblings yet back then.” I detect that already there’s some tough memories there that maybe haven’t been visited upon in a long time. We briefly discuss the topic of Jim’s biological father, but quickly move along to less intrusive topics. Jim is from a different generation that places a different value on privacy than that of mine and succeeding ones, and I respect the hell out of him for that. “That’s probably a story we don’t have to worry about telling.” 10-4.

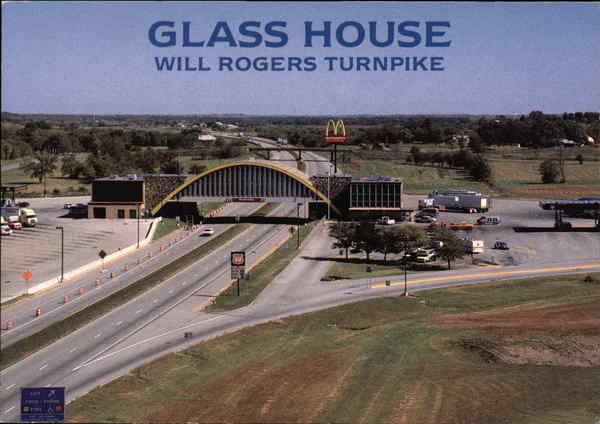

Nicknamed “Crossroads To Green Country” (presumably for its proximity to the greater Ozark territory), it’s not disparagement to point out that Vinita isn’t famous for a whole lot. In fact, it’s largest claim to fame could be a generations-old family-owned café that was once a staple on Route 66. For this reporter, Vinita is associated more with the “Will Rogers Archway”, an arch-shaped (you guessed it) building that spans across the Interstate 44 toll road, a sort of travel-stop-meets-small-market-airport-terminal vibe dominated by what is apparently the second largest McDonald’s restaurant (previously the largest, before some bastards in Orlando stoke the clown crown). I recall visiting this temple of cheeseburgers and potty breaks both as a child on family road trips from Kansas City to Dallas, but also many times while working for both Hall Brothers Racing and Team Bigfoot as an adult. In a somewhat sad turn of events (but pretty on-brand for the way the world is going these days), the iconic “Philipps 66” gas stations at the archway have been replaced by the unfortunately-named “Kum & Go” convenience store chain.

Pretty sure a tear can be seen occasionally rolling down the stone cheek of the Will Rogers statue inside the “concourse” every time someone makes a joke about the gas station’s name.

Migration & Assimilation – Oklahoma & California, 1956-1971

Like a small family of Okies fleeing the dust bowls of Oklahoma two decades behind schedule, Oldaker’s parents decided in the late 1950’s that indeed blue seas and greener pastures awaited them on the West Coast of California, the Los Angeles area specifically.

“I’m not entirely sure why my mom and step-dad decided to move us out to California, but I loved it out there,” he tells me, not without a bit of nostalgia in his voice. “It was really great back then, it was really awesome. I remember when I was 14 or 15, my best friend Bryan and I, we could ride public transportation all the way down to places like Venice Beach for like, 25 cents and just walk around, explore. We never had to worry about our safety then. I loved life out there at the time.”

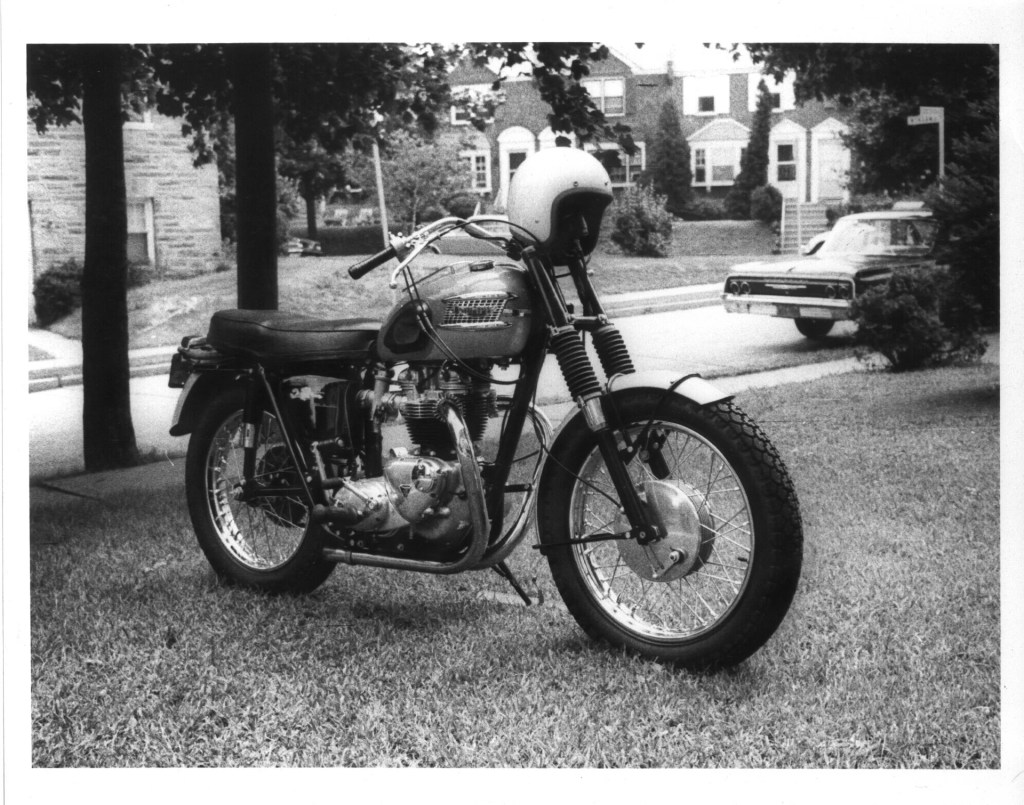

By age 16, Oldaker had discovered not only the joys of driving automobiles, but also the thrill and excitement of two-wheeled adventure in the form of various motorcycles. “I got my first motorcycle when I was 16, but it wasn’t really a motorcycle, it was more like a piece of crap Italian scooter!” he tells me with a laugh. “I had driven cars some around that time, but I didn’t get my own until I was probably 17 or 18. I liked motorcycles. Eventually I got a Triumph TT dirt 650, I loved that thing. I used to ride it all over the place, I’d ride it out of town way up to places like Big Sur, just all over the place.”

There’s a wistfulness in his voice for these old bikes of his that frankly I wasn’t expecting to hear from the guy who created, of all things, the first van-bodied monster truck (with diesel power no less.)

“One day when I was still in high school, instead of parking the bike in the back parking lot where things were a bit more secure, I decided to just park it right out front of the school. And when I came out later at the end of the day to head home, it was gone! I called the police right away; I even went door to door to all of the homes across the street trying to see if anyone had seen what happened. Eventually I found a little old lady who said she’d seen a car drive right up to the bike, and whoever was in the car just picked it up and threw it in the trunk and took off!”

The times, they were a changin’ in California.

“Right after the Triumph was stolen, I got a brand-new Honda Scrambler-type bike and I rode that for a good while before I tried ‘converting’ it into a ‘chopper’”, says Oldaker with another laugh. “I had no idea what the hell I was doing, I was just looking at pictures in magazines and tinkering in the family garage, trying to learn how to paint tanks and frames and stuff. This was right before I got into motocross bikes and racing, which I really got into pretty seriously.”

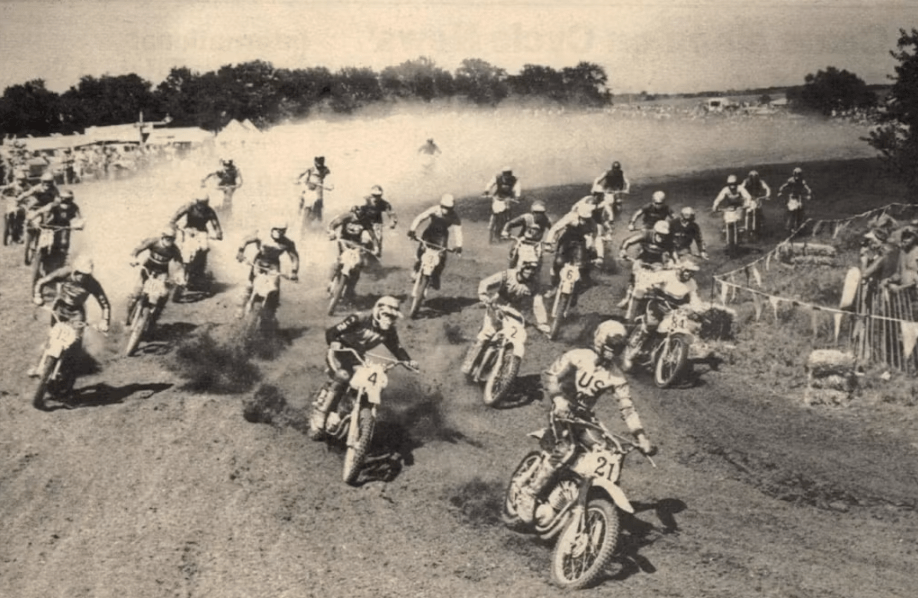

Speaking of serious, by the time Oldaker turned 18, American involvement in the Vietnam war had finally begun to draw down and concerns about being drafted to fight in far-away and unfamiliar lands gave way to more gleeful pursuits. “I got married when I was 18, and was motocross racing all I could while we were still living in California. There was a decent amount of motocross racing being held in California back then, but you really had to drive long distances to get to them.”

So, what did Jim haul himself and his bike around with back then? Enter A Big (soon to be) Orange Dodge. Just…not the one you’re thinking of.

“I had an old Dodge Town Wagon that I’d been working on for a long time and had fixed up to take my bike racing. I went to a lot of scrambles and motocross races with that thing, and often stayed in it at night. I’d just roll the bike up in the back and off to one side, lay down next to it and call it a night, just enough room for me and the bike.” This Town Wagon didn’t come already painted a proper custom color, so Oldaker shoved aside his bike projects in the garage to make room for the Dodge.

“So, the Town Wagon came to me plain white. At the time in California there were these stores called ‘Standard Paints’, and you could buy these big rattle cans of spray paint that had really wide spray patterns, so I bought a few cans of a shade of yellow I liked and I painted the Town Wagon that color. It turned out pretty good, there weren’t any runs or anything at least!”

Carry On, Wayward Son: Concordia – 1972 to 1979

“My best friend Bryan and his wife moved from California out to the Midwest in the early 70’s, and I guess I just felt compelled to follow them out that way. We’d been wanting to move back to the Midwest at some point, so we kind of followed them out to Concordia, Kansas,” recalls Oldaker. “I was getting really serious about the motocross stuff, and once Bryan told me about how many motocross tracks and events there were in the Midwest, I was pretty sold on moving.”

By that time, Concordia’s population was peaking at around 7,200 and the town boasted its own Yamaha, Kawasaki and Suzuki motorcycle shops. Shortly after relocating to the north-central Kansas hamlet, Oldaker had no trouble quickly securing some helpful (if not exactly lucrative) sponsorships from various parts suppliers and even bike dealers. “There were just so many races all over during the summer months, eastern Kansas, western Missouri, northern Oklahoma. I was able to get bikes at cost, parts at cost, it was a pretty good time for me as a rider.”

While the proliferation of scrambles and motocross events across the Midwest made for lively weekends for Oldaker and his then-wife Joyce, it was nowhere close to paying for itself much less the cost of their day-to-day lives.

“When we got to Concordia, my first ‘real’ job was working for the city, running a big road grader,” explained Oldaker. “But a buddy of mine, he worked at this place on the edge of town called ‘Combustion Engineering’, they made pipe fittings, huge compressed air equipment, a lot of heavy industrial stuff. I wanted to work there so I went out and applied and ended up getting my foot in the door as a painter, spraying all these huge pipes and fittings and such. Over time, you could bid on different jobs and they’d train you if selected.”

“So did you bid on any other jobs out there?” I asked Oldaker.

“Oh, yeah, I bid on a welding job. That’s how I learned to weld.” Seems like the kind of skill an eventual monster trucker could use. But that eventuality wasn’t yet a reality, and Oldaker had a lot of living to do before he decided to elevate his life atop 66” Goodyears.

Oldaker continued: “Combustion Engineering put me through Welding 1, 2 and 3 so by the time I left them I was a certified Welder 3, which is to say I was pretty decent at welding. After CE, I went to work for a chemical company hauling liquid fertilizers and such, driving a day-cab semi-tractor that had been fitted with a bed of sorts to haul barrels and containers of chemicals.”

By this point, Oldaker’s work history may seem fairly unremarkable, but his experience hauling chemicals was about to take a painful turn that would be life-altering for him in a number of ways, not the least of which was the effect it would have on his motocross pursuits.

“One day I was moving a 55-gallon drum of chemicals in the back bed of the truck I was operating for the chemical company, and while I had the barrel tilted on its edge to roll it towards the lift on the back of the truck, I must have hit a small rock or a snag or something, which caused the barrel to start to fall over. As it turns out, I was able to catch the barrel and save it from falling over, but I unbeknownst to me at that moment I’d hurt myself pretty good I the process.”

Dreading for him where this was going, I asked “What did you do? How bad did you injure yourself?”

“Well, I ruptured two discs in my back,” said Oldaker. I winced.

“That’s not very good buddy, that had to hurt like hell.”

“It hurt pretty good at times, and it left me seeing doctors, chiropractors and stuff like that for a few months. I had rented out a small shop on the edge of Concordia in an old filling station to do some painting and mechanical side jobs, so I had to work out of there quietly while trying to get better. Obviously, I couldn’t keep doing the chemical hauling job, and after a few months that company quit paying my insurance. I was still dealing with some of the side effects of the ruptured discs, but as soon as the insurance ran out the docs and chiros suddenly pronounced me ‘healed!’ and good to go. Except that I wasn’t.”

By the time Oldaker saddled one of his beloved motocross bikes back up and took to the track, he quickly realized he was in fact NOT good to go. After three or four months away from the track, he expected the challenge of getting back into riding shape to be difficult, but not insurmountable.

“My first time back at the track, holy shit, I couldn’t even get through the first moto. I was really wanting to get back to riding, honestly, I lived for riding motocross back then. And now I couldn’t. I was devastated. Just devastated.”

Oldaker’s focus shifted quickly (and painfully) away motorcycles as soon as he realized that his days of clearing doubles and eating up whup sections were behind him. Quite literally learning as he went and teaching himself from articles he found in car and hot rod magazines, Oldaker began eking out a living on the fringes of Concordia in his little rented shop by painting customer cars, as well as dabbling in some mild customizing. Eventually, he would trade off the Dodge Town Wagon for a 2WD short-bed pickup truck. That practical if underwhelming ride was soon sold off and replaced with a similarly practical-yet-uninspired Dodge window van.

Thankfully for Oldaker, the revolving Wheel of [Used Van] Fortune would spin yet again during that short span of time, with the arrow landing on a soon-to-be-repurposed….dog hauler?

“Yep, this gal came through town and she showed dogs, that was her thing. She had a short-wheelbase GMC van that was four-wheel drive, so I jumped at the chance to trade her the Dodge window van for the GMC. That was my first 4WD van, and I loved it. It would go damn near anywhere.”

The residual smell of show dogs and patchouli oil (probably) notwithstanding, the GMC proved to be a game-changer for Oldaker, a sort of skeleton key that would open up a world of new opportunity for him in this new post-motocross world he found himself navigating. Jim wasted no time getting a custom paint job laid onto the GMC, along with his first valiant stab at a custom “show van” interior. Oldaker may have stumbled into the 1970’s custom van party halfway by accident, but once inside he wasn’t about to leave anytime soon. In fact, he was about to migrate from the back corner of the room to the center of the dance floor, stopping for a proverbial snifter of brandy along the way. Hey, is that a disco ball?

“Eventually, someone told me about this car show happening in Wichita,” Oldaker tells me, and I know we’re about to approach a turning point in his story. “I’d painted the GMC up real nice, done a full custom interior in it and everything so my wife and decided we’d haul it down to this car show being put on by a guy I’d never heard of named Darryl Starbird.”

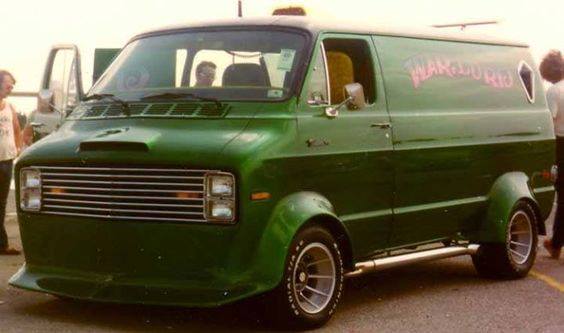

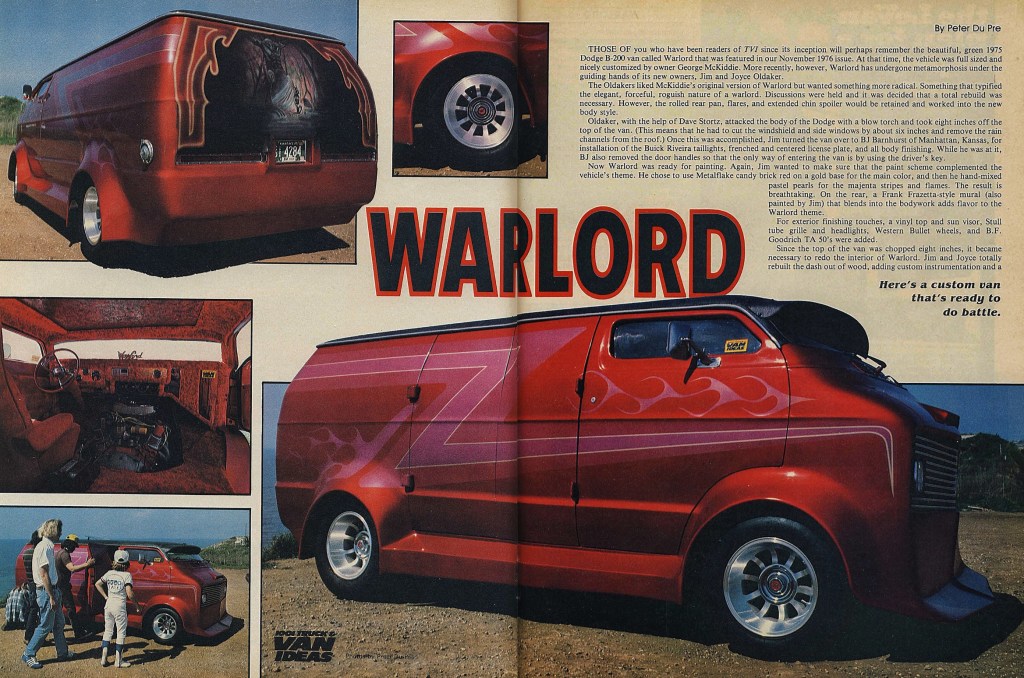

As fate would have it, Oldaker would meet some interesting characters during his first Starbird Car Show appearance, one of them being respected custom van builder George McKiddie. “We probably showed cars together for a couple seasons,” Oldaker tells me, continuing: “He (George) had this radical custom chopped Chevy van that was real nice, he showed it a lot and I really liked it. But then the next year, to the Starbird show, he brought in this van called ‘Warlord II’, which was a really extreme Dodge angle-chop van. I was in love, instantly,” says Oldaker. “To this day it is still the most beautiful van I’ve ever seen.” That’s high praise from a guy who was about to re-write the book on custom vans in a short period of time.

“So George, he tells me he’s looking to sell ‘Warlord II’, and like a fool I asked him how much, knowing it was going to be way out of my league. And it was,” laughs Oldaker. “Anyways, I found out that the fellow who’d purchased the first Warlord van, ‘Warlord I’, was interested in my 4WD GMC van. ‘Warlord I’ wasn’t chopped or anything, but he said he’d trade it to me for my van along with a ’69 Camaro project and a set of wheels to sweeten the deal. So, I made the trade.”

Once he got the “Warlord I” machine back to his shop in Concordia, Oldaker knew right away that he wanted to chop it. He reconnected with the aforementioned car show promoter Darryl Starbird, who in turn put in him contact with a couple friends of his who said they could chop his van for around $2,000. “That was a lot of money then, and it’s a lot of money now!” says Oldaker with a chuckle.

“Figure probably about eight grand these days,” I said.

“It felt like 15 or 20 grand to me then, and I couldn’t afford it,” Oldaker tells me, going on to confirm my suspicions that his stubborn resolve and willingness to figure out things for himself were going to be used to chop the van in question. “Once I figured out I wasn’t going to pay these guys to chop the fan for me, I found a magazine that featured a step-by-step DIY guide to chopping your own vehicle. So I just said ‘OK!’ and cut the damn roof off with my buddy Dave Stortz. We just winged it.”

From humans to pumpkins to vans, improvised woodshed craniotomies carry a degree of risk and uncertainty with them, not to mention a lengthy list of potential complications; and in the case of something like a full-size van, the need to re-size the windshield could probably be considered among the biggest hurdles that the good doctor and his cutting torch would be asked to consider. “It came out great!” says an enthused Oldaker, clearly still happy with his work even all these years later. “But….then I couldn’t find anyone to cut a windshield for it, which was a problem. I kept working on the rest of the van while calling around over time trying to find someone to cut some glass for it. Eventually I had everything done except for paint and glass when I got ahold of this guy up in Grand Island, Nebraska who said he could cut the windshield down for me,” says Oldaker.

“So, I bundled up in this big trench coat, threw on a pair of motocross goggles and drove ‘Warlord I’ with no windshield in it to Grand Island in the dead of the winter so this guy could cut it down for me.” Technically Oldaker did have a windshield in his possession, just not mounted in the front of the vehicle; rather, it was stashed in the back of the van and was presumably just as ice-cold as Oldaker himself was. And while resilient in so many ways, this otherwise fragile piece of cargo was about to complicate Oldaker’s day.

Apparently cutting a factory windshield down perfectly to fit a chopped and modified vehicle is more art than science. Also apparently, a glass windshield becoming brittle while riding in the back of an ice-cold van and subsequently cracking during the cutting process is more science than art. Having established those facts, the question then becomes “is duct-taping in the remnants of the broken windshield art, or science?” Whatever the correct answer is, to Oldaker it was simply necessity at that point.

More failed attempts at custom-cut windshields and subsequent duct-tape adventures would await Oldaker in the weeks to come, but finally “Warlord I” was properly completed with the addition of a cut-and-pasted windshield that wasn’t cracked, broken, or adhered together. Many car show appearances and awards would soon follow, and while Oldaker would continue to hone his self-taught paint-and-bodywork craft in Concordia, a wider world of automotive exploration back on the West Coast was soon calling his name, and so again was his best friend Bryan, too.

Everything In Transit…Again: Los Angeles area – 1979 to 1984

“My best friend Bryan and his wife decided to move back to the West Coast in ’79 or ’80, so Joyce and I said to hell with it and decided to move back too,” Oldaker tells me, going on to explain that “I couldn’t really race bikes anymore, and I couldn’t take my customizing business and stuff much further in the middle of Kansas, so we decided to see if we could try and do more of that stuff back in LA.”

By this point, Oldaker’s customizing abilities were not only exceptional, but had helped “Warlord I” gain serious notoriety in the custom show car (van?) circuit, including multiple magazine cover appearances and features. “I painted about anything I could in LA to help pay the bills, I even tried my hand at painting boats, which led to a sailboat, but that’s a whole other story. But when it came to the really intricate pinstriping, lettering, murals and all that, guys like Herb Martinez that worked with us were the real wizards. We had a guy named Ron who did murals that were just totally superior.”

“Wait, wait!” I interrupt. “You’ve got to fill me in on the sailboat stuff at some point” I practically demand of him, politely of course. Anyone who grew up on the “Battle/Return/War of the Monster Trucks” TV/VHS series remembers in “Return…” can remember when Jan Gabriel casually tosses out the factoid that “the young man [Oldaker] who lives on a sailboat when he’s not out with his monster truck” with absolutely ZERO explanation or context provided to help flesh that out. Oldaker assures me we’ll get to that later, and I intend to hold him to it.

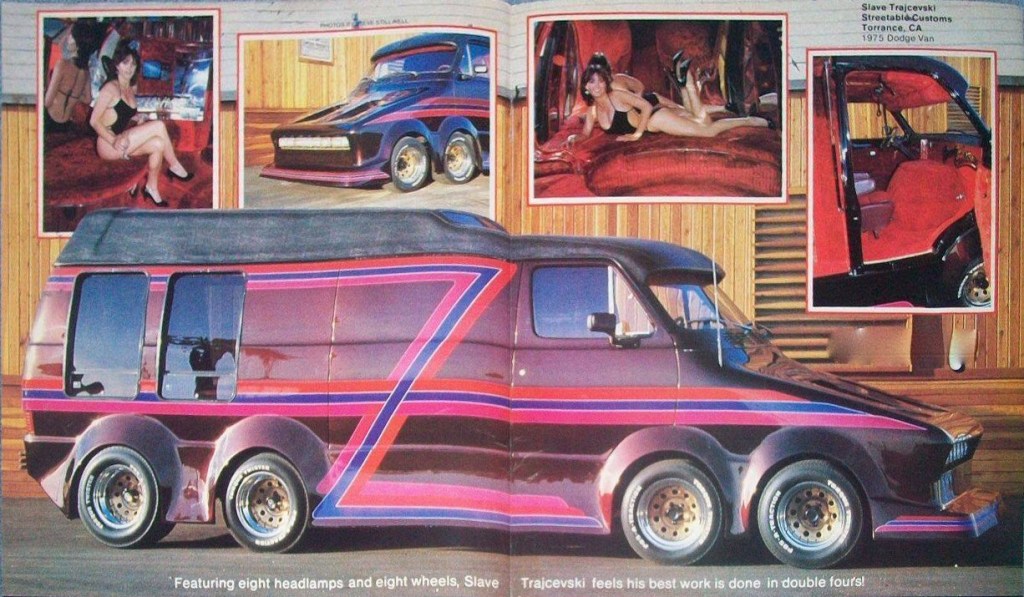

Once the Oldakers were reestablished in Southern California, Oldaker tells me how a van magazine editor/friend “hooked us up with this Yugoslavian fellow named Slavé Trajecevski who was trying to build a custom double-tandem-axle Dodge van out in the LA area. We had him bring the van over and while he’d managed to chop and stick weld stuff together, he wasn’t really a body man and he was seeking some help in that department. So, I flew my buddy BJ Barnhurst out from Kansas to help fix up the bodywork, do the custom flares and front end, all that stuff.”

Long-time collaborators, Oldaker and Barnhurst had recently received a good bit of press for their efforts on “Warlord I” via the June 1979 issue of the creatively-named “Truck & Van Ideas”; but after the debut of the extremely radical “Eight Is Enough” double-tandem project, the Oldaker/Trajecevski friendship-collaboration would take off to new heights as the demand for both their skills and imagination grew rapidly in the LA area and beyond.

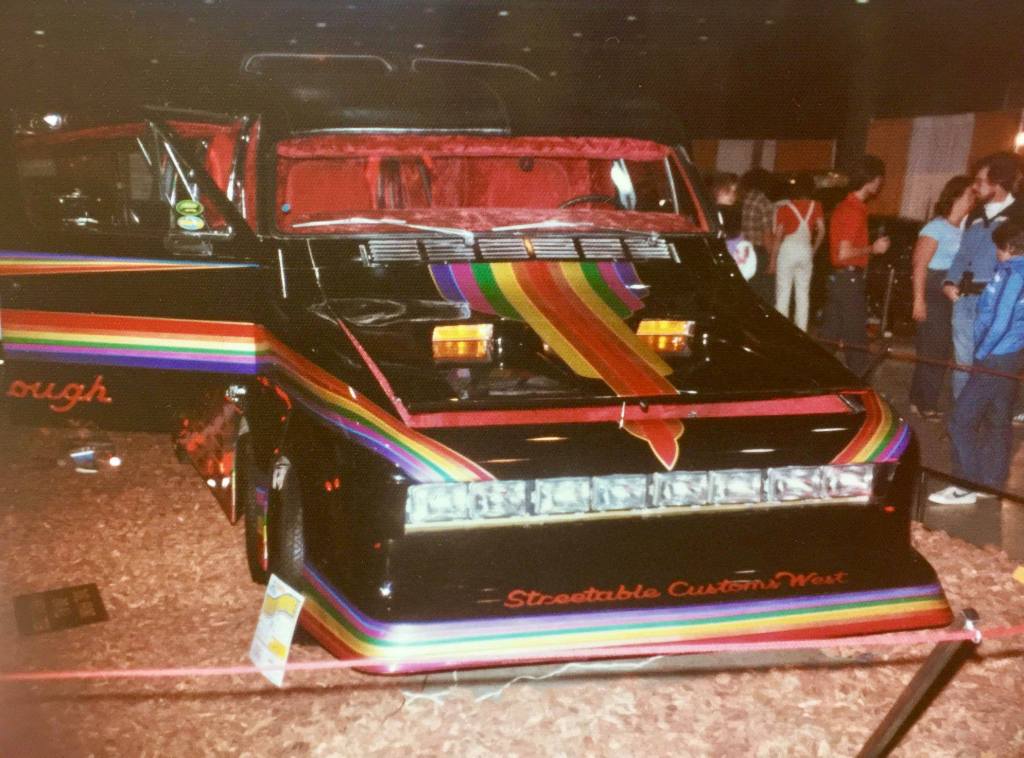

“We were working on stuff like this out in our driveway in front of the house, and people would of course see us doing these crazy vehicles up. Pretty soon, I don’t know if word spread or people just happened to be driving by or what but people would start asking us to take on projects for them that they weren’t able to do. Eventually we had to rent out what had been an old body shop from the 1950’s over in Torrance to keep up with the demand and the scope of some of these custom projects.”

Not even five miles inland from the mighty Pacific Ocean and the sandy shores of Redondo Beach is where you could have found Oldaker and Trajecevsky’s new venture, Streetable Customs. Having been constructed originally as a body shop in the 1950’s, their newfound workshop had recently just escaped by only a few blocks from being consumed by the Honda Corporation in 1981 when it scooped up 76 acres’ worth of industrial land in Old Torrance for what would eventually become their new North American headquarters by decade’s end.

“When Slavé and I teamed up to form Streetable Customs, we were doing a lot of really radical vehicles but they were all, you know, streetable!” Oldaker recounts with a chuckle. “No fiberglass tricks or anything, we were doing basically everything with metal, steel. And by then I was painting pretty much everything too, even murals and lettering and stuff.”

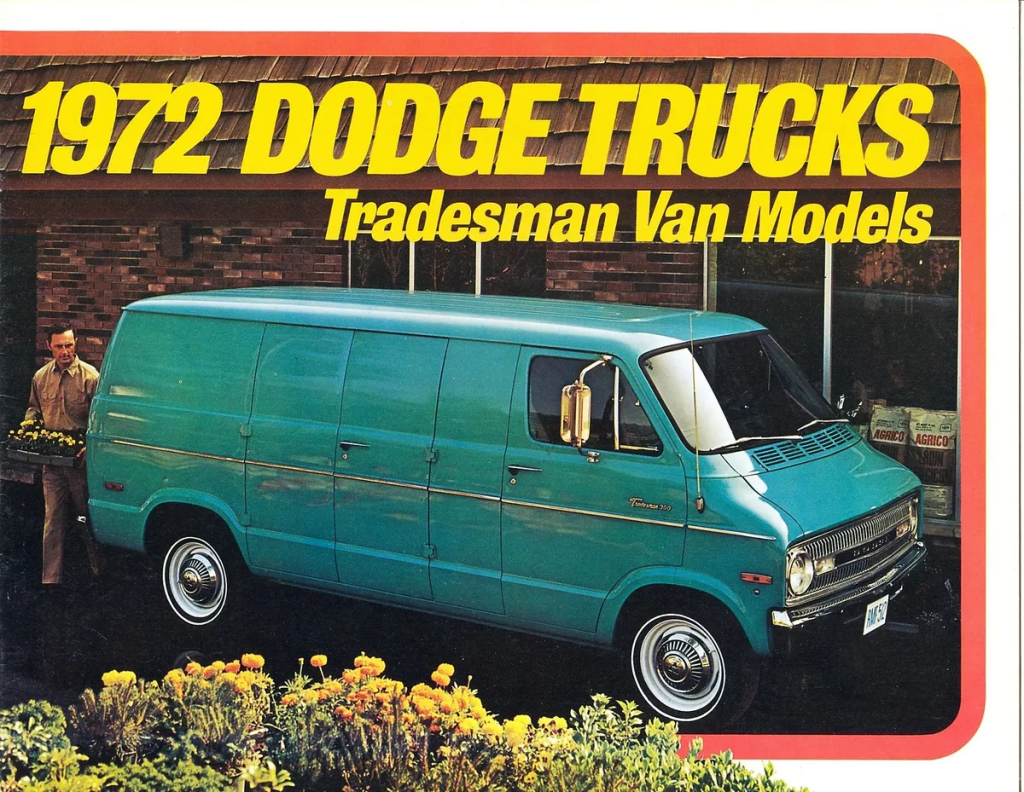

Flashing back to his time in Kansas as he attempted to regain his motocross career after his work injury, Oldaker explained that “I’d bought my father-in-law’s 1972 Dodge Tradesman van when I’d tried to go back to racing, since I’d gotten rid of the Dodge Town Wagon by then. When we moved back to California, everyone was running around in custom stuff they drove daily but all I had was the Tradesman van and a ’69 Volkswagen. That wasn’t going to cut it for me, especially with Streetable Customs being my business.”

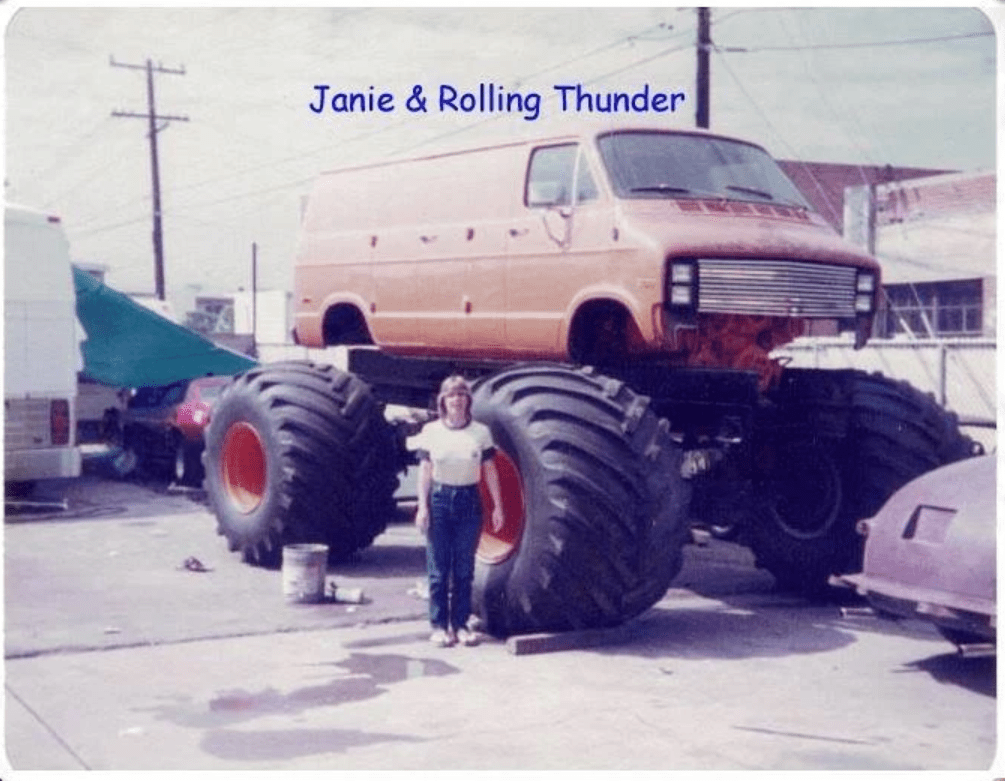

By now it was 1984 and while the bulk of SoCal custom car culture was centered on the lowered, the slammed and the chopped, Oldaker decided he’d built a new four-wheel drive van to help stand out from the crowd, using the tired-but-willing Tradesman van as the basis for the project. After sourcing a donor vehicle for the 4WD running gear, Oldaker thought he was all set and ready to reach for the sky with his latest project. And then suddenly his goals got a bit loftier, courtesy of a customer who came armed with a magazine and a wild idea.

“This customer came up to me one day with a magazine that had this big blue Ford truck on the front, it was massive, and it was called ‘Bigfoot’. They asked me ‘Why don’t you build one of these?’ So I asked myself ‘Yeah, why don’t I build one!?” Oldaker’s slightly mischievous chuckle as he recalls this pivotal moment to me in 2024 only hints at the mischief, laughter, and headache that was soon to be ahead of him all those years ago in 1984.

When Thunder Rolls: Torrance – 1984

In the days before the internet and social media, it would seem that the venerable print medium of “the magazine” might as well have been called “The Oracle” for ambitious gearheads and customizers like Jim Oldaker and his crew at Streetable Customs. After all, there was no Chilton’s manual for how to chop the roof on an 8-wheeled van or build a monster truck from scratch. Magazines, on the other hand, offered some pretty compelling information for the resourceful fabricator.

Shortly after being introduced to photographic proof of “Bigfoot”, Oldaker was steered in the direction of potential monster truck parts by yet another customer happy to helpfully project some ambitions onto Oldaker. “They showed me this old military 5-ton truck that had been converted to a water truck, maybe to be used to help fight fires or just water down a dusty jobsite or what have you. Anyways, I climbed around it and right away I was fixated on the Rockwell 5-ton axles under it, and I thought ‘Well hell, that looks just like the ones under the trucks in the magazines!”

While the truck in question was technically “complete”, it had had suffered some fire damage during a union dispute of some kind at the construction site where Oldaker had discovered it via his customer. Despite being mostly intact, it was also mostly immobile so Oldaker had it towed to Streetable Customs to begin his crash-course in Preliminary Monster Truck Assembly at Monster Truck University, as taught by Professor Magazine Rack.

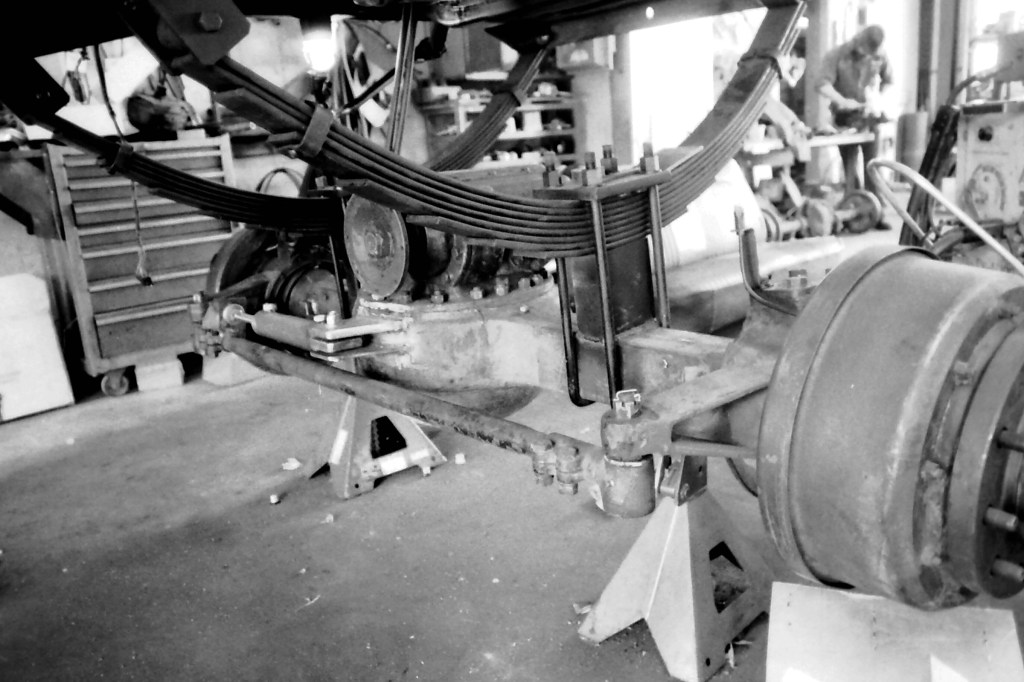

After removing and discarding the unnecessary bits like the water tank and bodywork, Oldaker set about deleting one of the rear axles and shortening the frame to a length that would match the 127” wheelbase required to match his Tradesman van body. As the donor truck had tandem rear axles, they would actually both be deleted and replaced with a steering axle from the front of another similar truck, so that Oldaker’s new creation would be equipped with front and rear steering axles, as any good monster truck should be.

The water truck’s steel straight-rail frame was kept, but custom-fabricated sub-frame pieces were added at all four corners to act as risers for the frame and mounts for the repurposed water truck leaf springs and shock absorbers below, all of which would allow the van body to ride properly above the tires instead of trying to squeeze between them width-wise. The renowned military parts barons at Boyce Equipment in Utah took delivery of the unwanted 5-ton Rockwell rear axles from the truck as well as the steering axle from the truck’s front end and in return shipped a pair of fully-rebuilt Rockwell 5-ton steering axles that were as optimized as they could be at the time for monster truck use, complete with 6.44:1 gearing and Detroit lockers for both axles, something Oldaker figured he’d probably need sooner rather than later.

“I really had no idea what exactly I was doing with all of this stuff, I was just figuring it out the best I could as I went along. But a couple times down the road that was going to bite me.”

Give the time and budget constrictions Oldaker found himself operating under, he opted to marry convenience with uniqueness by relying on the water truck’s existing engine and transmission combination for mechanical motivation. By skipping the common monster truck mathematic formula of “blown big-block V-8 plus 3-speed automatic transmission” and instead keeping the two-stroke 6-71 Detroit Diesel “Screamin’ Detroit” inline 6-cylinder bolted into the frame with the accompanying 5-speed Spicer manual transmission securely attached, followed by the requisite military 5-ton transfer case to separate power to both axles. Ironically, the van’s Detroit powerplant cubed out at exactly 426ci of displacement, but a member of the Chrysler Hemi family it most certainly was not.

Of interest to gearheads who may not be familiar with the Detroit 71 Series of diesel engines (named so for the 71 cubic inches-per-cylinder of displacement the series utilized), most all came equipped with what we now call a Roots-type supercharger fitted as part of the induction system, but not in the “conventional” way we’ve seen them used on racing and hot rod engines for decades. Rather, the supercharger (or “blower) was used to charge the cylinders with air for combustion, as the design of these 2-stroke diesels were such that they could not naturally draw in combustion air. All 71-series Detroits utilized “uniflow scavenging”, with the Roots-type blower providing slightly pressurized air for combustion into special passages in the engine block and via ports in the cylinder walls. Spent gasses from the combustion stroke would then exit through pushrod-activated poppet valves in the cylinder head. Later models eventually were given turbochargers that in turn fed into the superchargers to help boost power, resulting in the somewhat ludicrous-sounding label “Turbo-SuperCharged”; and I think we can all agree that would be a kick-ass name for an old Judas Priest song. But I digress…

Call it cheap, call it efficient, call it whatever you want, but Oldaker guaranteed virtually by default that his new monster creation would be unique among the growing hordes of imitators, and that’s without even taking the van body into consideration. While Jeff Dane’s Continental diesel engine-equipped “King Kong” might have been the first smoke belcher in monster truck history, Oldaker’s quirky 2-stroke screamer tucked under his glowing orange van body did a lot more to stand out from the crowd.

Speak of the van body, it would of course meet the wrath of the cutting torch and the welder in this reimagined Frankenstein’s laboratory. The interior of the van was stripped (what little there was at the time) and the doghouse area was cut out to create the cavity needed to accommodate the massive Detroit Diesel powerplant and Spicer gearbox. Rumor has it that when the van’s interior was finally given the full show-van treatment, it took two carpet stores’ worth of shag to fully cover the doghouse and transmission hump.

As the van body was essentially a one-piece unit, it would not be able to flex with the frame when under load during car crushes or climbing obstacles (compared to a standard pickup truck, which is basically a 3-piece unit consisting of front clip, cab, and bed that can flex somewhat independently) so to avoid the body literally being torn apart, Oldaker devised a spring-mounted subframe with mounts located forward of the rear axle and aft of the front axle, helping the van body to move independently of the main truck frame. From an interior standpoint, the plush, luxuriously-appointed show-van furnishings would have to wait until Oldaker’s time and budget caught up to the project. Shag carpet and televisions might not have been installed yet, but there were more notable aspects to the van’s interior that caught my attention while listening to Jim recount the building of the machine.

“Since we used the diesel and the stick-shift out of the water truck for the monster truck, we had to remove and re-do a lot of the dog house area to make room for everything. And compared to a small-block V-8, the diesel and the transmission took up a lot more space and sat way farther back under the floor. So that made for a pretty awkward gear shift lever, it was set way back kind of behind the driver and it had a long lever on it and an even longer throw between shifts. I’m not kidding when I say it must have been a two or three-foot throw between second and third gears.”

Like I said, skipping the big-block 440 and the 727 automatic transmission in favor of a howling 2-stroke diesel and a manual gearbox with a shifter throw longer than a King Crimson tune was indeed going to make this a truly unique machine.

Staying true to his roots as supremely talented custom painter of custom vans, Oldaker set about ensuring his new leviathan was as visually striking as it was mechanically unique. Despite having airbrushed his signature on many a layered and complex paint jobs, murals and graphics schemes over the years, Oldaker instead pivoted and went in the opposite direction. “Corvette Burnt Orange Metallic” was the color choice that would grace the re-born Tradesman, a color that Oldaker had long been fond of and had sprayed on a number of other vehicles he’d owned and driven.

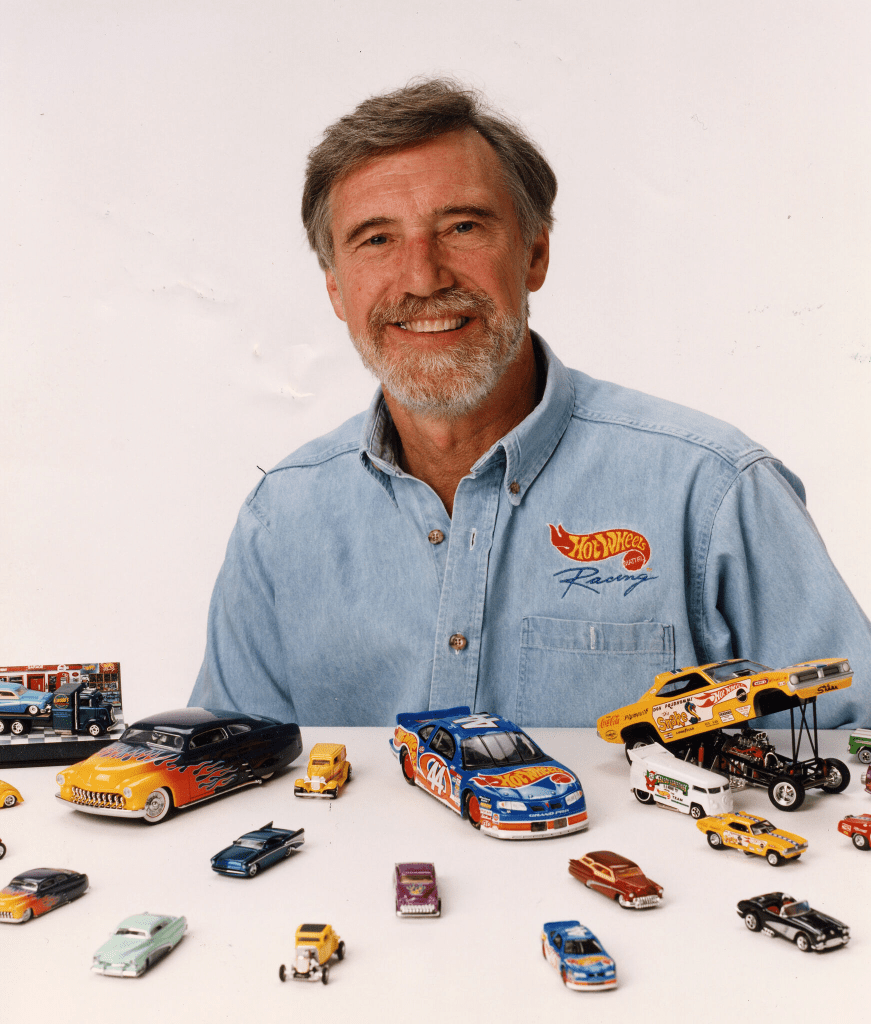

Inspired by the name of a book that had stuck with Oldaker for some years, the newborn monster van was appropriately christened “Rollin’ Thunder”. Custom painted and airbrushed graphics soon followed, depicting a cartoon version of the van crushing the words that made up its name. The original “Rollin’ Thunder” artwork was designed by the legendary “Mr. Hot Wheels” himself, Larry R. Wood of Redondo Beach, CA. Over the course of his 50+ years of work with Hot Wheels, Wood created some of the most iconic die-cast cars of all time and was inducted into both the Die-Cast Hall of Fame (inaugural class, 2009) and the Automotive Hall of Fame (class of 2023). Pretty hard to argue with those credentials, and it really says something about Oldaker’s status and connection in the SoCal custom car community that he was able to pull a guy like Wood to design the Rollin’ Thunder iconography.

It is impossible to not fall in love with the cartoon on the side of the van, it’s a piece of art that I wish I could have seen in person and to me is a worthy peer of the Dan Patterson-designed cartoon trucks that graced the bedsides of the Bigfoot family of trucks in the 1980’s. While early on the van sported only the “Rollin’ Thunder” graphics, it would soon receive additional touches that tastefully paid tribute to the van’s newly given name. A large wrap-around orange lightning bolt theme with blue, yellow and white outlines would eventually be added, combining with the existing lettering and cartoon truck to form what is inarguably the most iconic of the three Rollin’ Thunder liveries. This livery’s iconic status would eventually be immortalized by appearances in the “Return of the Monster Trucks” TV/VHS special as well as a 1:64th scale Matchbox monster truck toy, among many other media appearances.

It was only a matter of time before the paint was dry, the fluids were topped off and the Detroit Diesel inside Rollin’ Thunder would roar to life, ready to climb atop and crush untold numbers of junk cars for thousands of adoring fans across the country. Was Oldaker himself ready to crush cars, though? Was his newly-built monster-on-a-budget up to the task? Or would mechanical woes and inexperience leave the bright orange albatross struggling on the sidelines? Only time would tell, but before Rollin’ Thunder could prove or disprove itself to the public, Oldaker had a trip to make over some crush cars in a different monster.

Stay tuned for part two of the OSMT Original “Thunder & Smoke: The Jim Oldaker Story”!